浮世绘(日语:浮世絵/うきよえ Ukiyoe */?)是17至19世纪兴盛于日本的一种艺术表现手法。创作者制作了各种题材之木雕版印刷画和手绘作品(肉笔浮世绘),主要题材有女性美人、歌舞伎演员、相扑选手、历史场景、民间故事、旅行场景、风景、植物、动物、情色描绘等。

1603年,江户成为日本政治权力中心之德川幕府的根据地。处于社会秩序底层的町人阶级(商人、手工业者和工人)从城市的高速经济增长中获益最多,开始沉迷和光顾歌舞伎、艺伎、花魁等所在之娱乐活动地区(游廓);浮世绘(“浮动的世界”)一词用来描述这种享乐主义的生活方式。印刷或绘画的浮世绘作品在町人阶级中很受欢迎,他们已经变得足够富有,可以用之来装饰自己的住家。

最早的浮世绘作品出现于1670年代,有菱川师宣的画作和以美丽女性为题材的单色版画。彩色印刷品而后逐渐出现,起初仅限于特殊委托。到1740年代,奥村政信等艺术家开始使用多个木版以印刷颜色区块。在1760年代,铃木春信的“锦绘”取得成功,全彩色制作开始成为标准,每幅版画使用 10 个或更多色块制作。 一些浮世绘艺术家专门制作绘画,但大多数作品都是版画。 艺术家很少雕刻自己的木版进行印刷; 相反,生产由设计版画的艺术家、切割木版的雕刻师、将木版上墨并压在手工纸上的印刷商,以及资助、推广和发行作品的出版商分别进行。由于印刷是手工完成的,印刷商能够实现机器无法实现的效果,例如印版上颜色的混合或渐变。

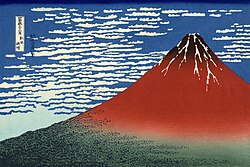

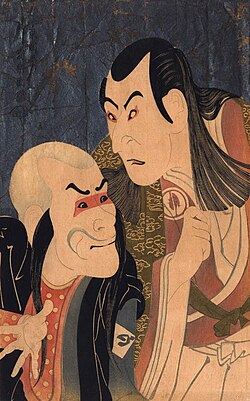

18世纪末之鸟居清长、喜多川歌麿和东洲斋写乐等代表性创作者的女性和演员题材之肖像画备受重视。19世纪也见证了浮世绘之杰出创作之延续,葛饰北斋创作了日本最著名的艺术作品之一《神奈川冲浪里》,还有歌川广重的《东海道五十三次》。在这两位代表性创作者过世不久后,在1868年明治维新之后的技术发展和社会现代化进程中,浮世绘的产量急剧下降。 然而,在20世纪日本版画再度兴起:“新版画”流派针对西方社会对日本传统场景版画的兴趣进行商业创作,“创作版画”运动促进了个人主义作品的出现,该类创作由一位艺术家独力设计、雕刻和印刷。自20世纪末以来,版画一直延续著个人主义风格,通常采用从西方引进的技术制作。

浮世绘是19世纪后期形成西方对日本艺术看法的核心,尤其是葛饰北斋和歌川广重的风景画。1870年代起,日本主义成为一股显著的潮流,对埃德加·德加、爱德华·马奈、克劳德·莫奈等早期印象派画家,以及文森特·梵高等后印象派画家和亨利·德·图卢兹-罗特列克等新艺术运动艺术家产生了深远的影响。

历史

“浮世绘”这一名词最早出现于1681年(天和元年)日本发行的俳谐书《各种各样的草》[1]。“浮世”一词是日本中世以来的佛教概念中相对于净土的充满忧虑的现世。它所指称在尘俗人间的漂浮不定,衍伸为一种享乐的人生态度,可以尽显于浮世绘里欢乐荣景的华丽刻划。

浮世绘画师以狩野派、土佐派出身者居多,这是因为当时这些画派非常显赫,而被这些画派所驱逐、排斥的画师很多都转向浮世绘发展所致。

初期

明历大火(1657年3月2日)至宝历年间(1751年~1763年)。此时期的浮世绘以手绘及墨色单色木版画印刷(称为墨折绘)为主。

17世纪后半,后世尊为“浮世绘之祖”的菱川师宣将画面从册装图书的形式中彻底独立出来,创造了单幅版画“一枚拓”,成为浮世绘的基本样式。

到了鸟居清信时代,使用墨色以外的颜色创作的作品开始出现,主要是以红色为主。使用丹色(红褐色)的称丹绘,使用红色的称红绘,也有在红色以外又增加二、三种颜色的作品,称为红折绘。[2]

中期

明和2年(1765年)至文化3年(1806年)。锦绘在此时期诞生。

因为画历(絵暦)在俳句诗人及爱好者间十分受欢迎,明和2年开始有了画历交换会的社交活动。为因应这种大量需求,铃木春信等人以多色印刷法发明了东锦绘,浮世绘文化正式迈入鼎盛期。

由于多色印刷法需反复上色,因此开发出印刷时如何标记“见当(记号之意)”的技巧和方法,并且开始采用能够承受多次印刷的高品质纸张,例如以楮为原料的越前奉书纸、伊予柾纸、西野内纸等。另外在产能及成本的考量下,原画师(版下绘师)、雕版师(雕师)、刷版师(刷师,或写做折师)的专业分工体制也在此时期确立。

此时期的人物绘画风格也发生变化,由原本虚幻的人偶风格转趋写实。

安永年间(1772年—1780年),北尾重政写实风格的美人画大受好评。胜川春章则将写实风带入称为“役者绘”的歌舞伎肖像画中。之后著名的喜多川歌麿更以纤细高雅的笔触绘制了许多以头部为主的美人画。

宽政2年(1790年),幕府施行了称为“改印制度”的印刷品审查制度,开始管制印刷品的内容。宽政7年(1795年),因触犯禁令而被没收家产的出版家茑屋重三郎为了东山再起,与画师东洲斋写乐合作,出版了许多风格独特、笔法夸张的役者绘。虽然一时间造成话题,但毕竟风格过于特异,并未得到广泛回响。同时期最受欢迎的风格是歌川丰国所绘的《役者舞台之姿绘》的歌舞伎全身图系列。而歌川的弟子们也一跃形成浮世绘的最大画派—“歌川派”。

后期

喜多川歌麿死后,美人画的主流转变为溪斋英泉的情色风格。而胜川春章的门生葛饰北斋则在旅行话题盛行的带动下,绘制了著名的《冨岳三十六景》。受到葛饰北斋启发,歌川广重也创作了名作《东海道五十三次》、《名所江户百景》。此二人确立了浮世绘中称为“名所绘”的风景画风格。

在役者绘方面,歌川国贞师承歌川丰国,以更具力道的笔法绘制。另外,伴随着草双纸(类似现代的漫画书)所引发的传奇小说热潮,歌川国芳等人开始创作描绘武士姿态的“武者绘”。歌川国芳的水浒传系列非常受欢迎,在当时的日本引爆了水浒传风潮。

在嘉永6年(1853年)所刊行的《江户寿那古细见记》中有一句“豐國にがほ(似顔繪)、國芳むしや(武者繪)、廣重めいしよ(名所繪)”,简单而直接地为此时期的风格做了总结。

终期

安政6年(1859年)至明治45年(1912年)。

此时期因为受到美国东印度舰队司令佩里(或译:培里)率领舰队强行打开锁国政策(此事件日本称为“黑船来航”)的冲击,许多人开始对西洋文化产生兴趣,因此发轫于当时开港通商之一的横滨的“横滨绘”开始流行起来。

另一方面,因为幕末至明治维新初期社会动荡的影响,也出现了称为“无残绘(或写做无惨绘)”的血腥怪诞风格。这种浮世绘中常有腥风血雨的场面,例如歌川国芳的门徒月冈芳年和落合芳几所创作的《英名二十八众句》。

河锅晓斋等正统狩野派画师也开始创作浮世绘。而后师承河锅晓斋的小林清亲更引入西画式的无轮廓线笔法绘制风景画,此画风被称为光线画。

歌川派的歌川芳藤则开始为儿童创作称为玩具绘的浮世绘,颇受好评,因而被称为“おもちゃ芳藤(おもちゃ为玩具之意)”。

但是由于西学东渐,照相技术传入,浮世绘受到严苛的挑战。虽然很多画师以更精细的笔法绘制浮世绘,但大势所趋,终究无法力抗历史的潮流。

其中,月冈芳年以非常细腻的笔法和西洋画风绘制了许多画报(锦绘新闻)、历史画、风俗画,有“最後の浮世絵師”之称。月冈本人也鼓励门徒多多学习各式画风,因而产生了许多像镝木清方等集插画、传统画大成的画师,浮世绘的技法和风格也得以以不同形式在各类艺术中继续传承下去。

题材与种类

- 是浮世绘最主要的题材,以年轻美丽的女子为题材。主要是描绘游女(妓女)和茶屋的人气看板娘(招牌女郎),后来也有街头美女的题材。

- 以著名的歌舞伎演员为题材。肖像画与广告传单的形式都有。

- 以滑稽有趣的事物为题材,常见拟人化的手法,也可包括下文的鸟羽绘。另外有时也有讽刺画的性质,但还是以娱乐性为主。

- 即绘画教学手册,有各式各样的题材,定义和现代的漫画不同。

- 春画、あぶな繪

- 春画是以性爱场面及相关事物为题材,亦可见将性器拟人化的手法。这类画作在实用上也有做为情趣用品目录及嫁妆之用。在当时的乡村地区提到锦绘的话,多半就是指春画。あぶな絵则是较为含蓄的情色画,因1722年德川吉宗禁止了春画而出现,在宝历年间达到巅峰。有美人出浴、罗衫轻解等题材。

- 描绘以东京地区为中心急速发展的西洋事物,如建筑物、西装和娱乐方式等。因其使用有毒矿物颜料苯胺红,又被称为“红绘”。

- 除了满足当时无迁徙和旅行自由的民众对名山秀水的憧憬之外,也有做为旅行手册的应用。

- 花鸟绘

- 以花、鸟、虫、鱼、兽为题材。

- 以历史上著名的事件为题材。明治维新后,为了更加巩固天皇家的正统性,也有以历代天皇为主题的创作。

- 取材自既有的历史故事,但以当时的人地事物仿套。

- 以相扑为题材,也有相扑力士的肖像画。

- 一张纸上区分成数个大小不一的区块,各区块中皆有独立的主题。张交绘常常是多位画师共同完成的作品,因此同一张画上可以看到多位画师的画风。

- 名人去世时的追悼肖像画。

- 以小孩子游玩时的情景为题材。

- 疱疮绘、麻疹绘

- 绘在团扇上的装饰图。

制作方法

浮世绘是版画的一种,由原画师、雕版师、刷版师三者分工协力完成。原画师将原图完成后,由雕版师在木板上雕刻出图形,再由刷版师在版上上色,将图案转印到纸上。要上多少色就必须刻多少版,因此颜色越多,制程就越繁杂。虽然是协力完成的作品,但一开始只有原画师才能落款,后来也有刻版师的落款。另外由于幕府实行的审查制度,准许刊行的浮世绘上也会有幕府审查标章及刊行者的印记。

浮世绘的制作过程可分为5个步骤。

- 一、绘制原图

由原画师构思设计,然后以黑色描绘轮廓。古时此步骤完成后即需送交幕府审查内容。审查通过的话,幕府就会盖上合格印记。

- 二、雕刻墨板

审查过的原图交给雕版师后,雕版师会将原图反过来贴在山樱木制的木板上并浮雕出图案,此板即称为墨板。为应付将来反复印刷、多次上色的制程需要,日本人发明了标示“見當(记号之意)”的方法。该方法的起源有2说:

- 1744年出版物批发商上村吉右卫门所发明。

- 1765年一名叫做金六的刷版师所发明。

- 三、选定色彩

墨板交给刷版师后,刷版师会用薄美浓纸印出做为雕刻色板的底图之用的校合折数张,张数则依原画师计划使用的颜色数目而决定。原画师会在校合折上以红笔指定心中所构思的色彩。

- 四、雕刻色板

校合折交给雕版师后,雕版师会以同样的方法雕出所需的色板。

- 五、刷版

墨板和色板都到齐后,刷版师便开始一色一色反复印刷上色。依画面所用的颜色多寡,印刷次数也不同,一般约需刷10到20多次。色彩重叠的部分以由淡而浓、由小(面积)而大的原则处理。

画作价格

浮世绘过往是日本平民能负担起的艺术欣赏,价格往往与“一碗荞麦面”相同。价格依时代会有所不同,但从当时的史料、日记、游记中,可以看出大致价位。在19世纪初,大幅面锦绘的浮世绘价格约为20文钱,到了19世纪中叶,也是在20文范围内。据记载,德川幕府末期的荞麦面大约是 16 文钱,与当年浮世绘作品大约等价位。[4]

例如,经常被各种书籍所引用的“荏土自慢名产杖”浮世绘,是以歌舞伎为题材的绘图小版本,在1805年所印制的。一般认为当时的红绘只有几种颜色,而且纸质略逊一筹,所以价格便宜, 2张只卖16文钱。依据文书记载,在1795 年锦绘出售价格约在20 文,新作只能卖16-18文钱。在天保年间的改革下,浮世绘的着色次数被限制在 7 或 8 次,价格限制在每张 16 文钱或更少,以致绘者无利可图。1843年“藤冈屋日记”的文字记载,使用大量深红色的神田祭的锦绘,只以16文钱卖出。当时的日记中写道:卖的越多,赔的越多。 到了幕府末年及明治初年,浮世绘价格已经拉高,一般平民不会轻易购买。[5]

到了明治时代,政府修订出版条例,强制标价,浮世绘的价格就清晰可查。一般来说,浮世绘作品定价2钱;如果是需要花费时间和精力的作品,则需另加1钱出售[6]。

影响

19世纪中期开始,欧洲由日本进口茶叶,因日本茶叶的包装纸印有浮世绘版画图案,其风格也开始影响了当时的印象派画家。

1865年法国画家布拉克蒙(Felix Bracquemond)将陶器外包装上绘的《北斋漫画》介绍给印象派的友人,引起了许多回响。

梵高可能是著名画家中受浮世绘影响最深的人。1885年梵高到安特卫普时开始接触浮世绘,1886年到巴黎时与印象派画家有往来,其中马奈、罗特列克也都对浮世绘情有独钟,例如马奈的名作《吹笛少年》即运用了浮世绘的技法。同样地,梵高也临摹过多幅浮世绘,并将浮世绘的元素融入他之后的作品中,例如名作《星夜》中的涡卷图案即被认为参考了葛饰北斋的《神奈川冲浪里》。

法国印象派画家莫内对葛饰北斋名作神奈川冲浪里推崇备至,这幅作品至今仍收藏于他在吉维尼的故居。

无独有偶,在音乐方面,古典音乐的印象派作曲家克劳德·德布西亦受到《神奈川冲浪里》的启发,创作了交响诗《海》(La Mer)。

浮世绘的艺术风格让当时的欧洲社会刮起了和风热潮(日本主义),浮世绘的风格对19世纪末兴起的新艺术运动也多有启迪。

及后,亦演变出各类分支,2019年,来自现代浮世绘派系的4位日本艺术家Horihiro Mitomo、Ukiyoemon Mitomoya、Horitatsu及Bang Ganji,于香港K11 Art Space举办以“现代浮世绘”为主题的作品展[7]。

代表画师

注释

参考文献

- ^ 日本浮世絵協会編『原色浮世絵大百科事典』第六巻. 大修馆. 1982: 10.

- ^ 代代相傳的浮世繪技術——訪Adachi版畫研究所. nippon.com. [2017-01-10]. (原始内容存档于2021-03-23).

- ^ 浮世繪——江戶世風民情的寫照. nippon.com. [2017-01-10]. (原始内容存档于2019-05-03).

- ^ 安村敏信监修‘浮世絵図鉴 江戸文化の万华镜’平凡社〈别册太阳〉、2014年1月11日。ISBN 978-4-582-92214-1。 p. 180.

- ^ 根本进、永田生慈対谈“近代漫画のルーツは北斎”‘北斎美术馆4 名所絵’、1990年。 p. 146.

- ^ 岩切信一郎“明治期木版画の盛衰”‘近代日本版画の诸相’青木茂监修、町田市立国际版画美术馆编、1998年12月。 pp. 89–118.

- ^ 《K11 ART MATSURI 藝術祭》浮世繪展 限定鮪魚搪膠一日售罄. [2019-11-29]. (原始内容存档于2021-03-23).

学术期刊

- Fitzhugh, Elisabeth West. A Pigment Census of Ukiyo-E Paintings in the Freer Gallery of Art. Ars Orientalis (Freer Gallery of Art, The Smithsonian Institution and Department of the History of Art, University of Michigan). 1979, 11: 27–38. JSTOR 4629295.

- Fleming, Stuart. Ukiyo-e Painting: An Art Tradition under Stress. Archaeology (Archaeological Institute of America). 1985-11 / 1985-12, 38 (6): 60–61, 75. JSTOR 41730275.

- Hickman, Money L. Views of the Floating World. MFA Bulletin (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). 1978, 76: 4–33. JSTOR 4171617.

- Meech-Pekarik, Julia. Early Collectors of Japanese Prints and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum Journal (University of Chicago Press). 1982, 17: 93–118. JSTOR 1512790.

- Kita, Sandy. An Illustration of the Ise Monogatari: Matabei and the Two Worlds of Ukiyo. The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland Museum of Art). 1984-09, 71 (7): 252–267. JSTOR 25159874.

- Singer, Robert T. Japanese Painting of the Edo Period. Archaeology (Archaeological Institute of America). 1986-03 / 1986-04, 39 (2): 64–67. JSTOR 41731745.

- Tanaka, Hidemichi. Sharaku Is Hokusai: On Warrior Prints and Shunrô's (Hokusai's) Actor Prints. Artibus et Historiae (IRSA s.c.). 1999, 20 (39): 157–190. JSTOR 1483579.

- Toishi, Kenzō. The Scroll Painting. Ars Orientalis (Freer Gallery of Art, The Smithsonian Institution and Department of the History of Art, University of Michigan). 1979, 11: 15–25. JSTOR 4629294.

- Watanabe, Toshio. The Western Image of Japanese Art in the Late Edo Period. Modern Asian Studies (Cambridge University Press). 1984, 18 (4): 667–684. JSTOR 312343. doi:10.1017/s0026749x00016371.

- Weisberg, Gabriel P. Aspects of Japonisme. The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland Museum of Art). 1975-04, 62 (4): 120–130. JSTOR 25152585.

- Weisberg, Gabriel P.; Rakusin, Muriel; Rakusin, Stanley. On Understanding Artistic Japan. The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts (Florida International University Board of Trustees on behalf of The Wolfsonian-FIU). 1986 Spring, 1: 6–19. JSTOR 1503900.

书籍

- Addiss, Stephen; Groemer, Gerald; Rimer, J. Thomas. Traditional Japanese Arts And Culture: An Illustrated Sourcebook. University of Hawaii Press. 2006 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-8248-2018-3. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Bell, David. Ukiyo-e Explained. Global Oriental. 2004. ISBN 978-1-901903-41-6.

- Belloli, Andrea P. A. Exploring World Art. Getty Publications. 1999 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-89236-510-4. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Benfey, Christopher. The Great Wave: Gilded Age Misfits, Japanese Eccentrics, and the Opening of Old Japan. Random House. 2007 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-307-43227-8. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Brown, Kendall H. Impressions of Japan: Print Interactions East and West. Javid, Christine (编). Color Woodcut International: Japan, Britain, and America in the Early Twentieth Century. Chazen Museum of Art. 2006: 13–29 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-932900-64-7. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Buser, Thomas. Experiencing Art Around Us. Cengage Learning. 2006 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-534-64114-6. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Checkland, Olive. Japan and Britain After 1859: Creating Cultural Bridges. Routledge. 2004 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-203-22183-9. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Faulkner, Rupert; Robinson, Basil William. Masterpieces of Japanese Prints: Ukiyo-e from the Victoria and Albert Museum. Kodansha International. 1999 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-4-7700-2387-2. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Frédéric, Louis. Japan Encyclopedia. Harvard University Press. 2002 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5. (原始内容存档于2011-12-13).

- Garson, Alfred. Suzuki Twinkles: An Intimate Portrait. Alfred Music. 2001 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-1-4574-0504-4. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Harris, Frederick. Ukiyo-e: The Art of the Japanese Print. Tuttle Publishing. 2011 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-4-8053-1098-4. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Hibbett, Howard. The Floating World in Japanese Fiction. Tuttle Publishing. 2001 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-8048-3464-3. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Hillier, Jack Ronald. Japanese Masters of the Colour Print: A Great Heritage of Oriental Art. Phaidon Press. 1954 [2014-08-04]. OCLC 1439680. (原始内容存档于2020-09-20) –通过Questia.

- Hockley, Allen. The Prints of Isoda Koryūsai: Floating World Culture and Its Consumers in Eighteenth-century Japan. University of Washington Press. 2003 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-295-98301-1. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Honour, Hugh; Fleming, John. A World History of Art. Laurence King Publishing. 2005 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-1-85669-451-3. (原始内容存档于2020-08-19).

- Hughes, Glenn. Imagism & the Imagists: A Study in Modern Poetry. Biblo & Tannen Publishers. 1960 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-8196-0282-4. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Ishizawa, Masao; Tanaka, Ichimatsu. The Heritage of Japanese art. Kodansha International. 1986 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-87011-787-9. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Ives, Colta Feller. The Great Wave: The Influence of Japanese Woodcuts on French Prints (PDF). Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1974 [2014-08-04]. OCLC 1009573. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-02-24).

- Jobling, Paul; Crowley, David. Graphic Design: Reproduction and Representation Since 1800. Manchester University Press. 1996 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-7190-4467-0. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Kikuchi, Sadao; Kenny, Don. A Treasury of Japanese Wood Block Prints (Ukiyo-e). Crown Publishers. 1969. OCLC 21250.

- King, James. Beyond the Great Wave: The Japanese Landscape Print, 1727–1960. Peter Lang. 2010 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-3-0343-0317-0. (原始内容存档于2015-03-20).

- Kita, Sandy. The Last Tosa: Iwasa Katsumochi Matabei, Bridge to Ukiyo-e. University of Hawaii Press. 1999 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-8248-1826-5. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Kita, Sandy. Japanese Prints. Nietupski, Paul Kocot; O'Mara, Joan (编). Reading Asian Art and Artifacts: Windows to Asia on American College Campuses. Rowman & Littlefield. 2011: 149–162 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-1-61146-070-4. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Kobayashi, Tadashi; Ōkubo, Jun'ichi. 浮世絵の鑑賞基礎知識. Shibundō. 1994. ISBN 978-4784301508.

- Kobayashi, Tadashi. Ukiyo-e: An Introduction to Japanese Woodblock Prints. Kodansha International. 1997 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-4-7700-2182-3. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Lane, Richard. Masters of the Japanese Print: Their World and Their Work. Doubleday. 1962 [2014-08-04]. OCLC 185540172. (原始内容存档于2020-12-10) –通过Questia.

- Lewis, Richard; Lewis, Susan I. The Power of Art. Cengage Learning. 2008 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-534-64103-0. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Link, Howard A.; Takahashi, Seiichirō. Utamaro and Hiroshige: In a Survey of Japanese Prints from the James A. Michener Collection of the Honolulu Academy of Arts. Ōtsuka Kōgeisha. 1977 [2014-08-04]. OCLC 423972712. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Mansfield, Stephen. Tokyo A Cultural History. Oxford University Press. 2009 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-19-972965-4. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Marks, Andreas. Japanese Woodblock Prints: Artists, Publishers and Masterworks: 1680–1900. Tuttle Publishing. 2012 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-1-4629-0599-7. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Meech-Pekarik, Julia. The World of the Meiji Print: Impressions of a New Civilization. Weatherhill. 1986 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-8348-0209-4. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Merritt, Helen. Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: The Early Years. University of Hawaii Press. 1990 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-8248-1200-3. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Michener, James Albert. The Floating World. University of Hawaii Press. 1954 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-8248-0873-0. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Michener, James A. Japanese Print: From the Early Masters to the Modern. Charles E. Tuttle Company. 1959. OCLC 187406340.

- Munsterberg, Hugo. The Arts of Japan: An Illustrated History. Charles E. Tuttle Company. 1957 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 9780804800426. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Neuer, Roni; Libertson, Herbert; Yoshida, Susugu. Ukiyo-e: 250 Years of Japanese Art. Studio Editions. 1990 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-1-85170-620-4. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Noma, Seiroku. The Arts of Japan: Late Medieval to Modern. Kodansha International. 1966 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-4-7700-2978-2. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Ōkubo, Jun'ichi. カラー版 浮世絵. Iwanami Shoten. 2008. ISBN 978-4-00-431163-8.

- Ōkubo, Jun'ichi. 浮世絵出版論. Fujiwara Printing. 2013. ISBN 978-4-642-07915-0.

- Penkoff, Ronald. Roots of the Ukiyo-e; Early Woodcuts of the Floating World (PDF). Ball State Teachers College. 1964 [2014-08-04]. OCLC 681751700. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2017-09-02).

- Salter, Rebecca. Japanese Woodblock Printing. University of Hawaii Press. 2001 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-8248-2553-9. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Salter, Rebecca. Japanese Popular Prints: From Votive Slips to Playing Cards. University of Hawaii Press. 2006 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-8248-3083-0. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Screech, Timon. Sex and the Floating World: Erotic Images in Japan, 1700–1820. Reaktion Books. 1999 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-1-86189-030-6. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Seton, Alistair. Collecting Japanese Antiques. Tuttle Publishing. 2010 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-4-8053-1122-6. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Sims, Richard. French Policy Towards the Bakufu and Meiji Japan 1854–95. Psychology Press. 1998 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-1-873410-61-5. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Statler, Oliver. Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn. Charles E. Tuttle Company. 1959. ISBN 978-1-4629-0955-1.

- Sullivan, Michael. The Meeting of Eastern and Western Art. University of California Press. 1989 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-520-05902-3. (原始内容存档于2019-12-12).

- Suwa, Haruo. 日本人と遠近法. Chikuma Shobō. 1998. ISBN 978-4-480-05768-6.

- Takeuchi, Melinda. The Artist as Professional in Japan. Stanford University Press. 2004 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-8047-4355-6. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Winegrad, Dilys Pegler. Dramatic Impressions: Japanese Theatre Prints from the Gilbert Luber Collection. University of Pennsylvania Press. 2007 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-8122-1985-2. (原始内容存档于2020-08-19).

- Yashiro, Yukio. 2000 Years of Japanese Art. H. N. Abrams. 1958 [2014-08-04]. OCLC 1303930. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

- Yoshimoto, Mitsuhiro. Reexamining the East and the West: Tanizaki Jun'ichiro, 'Orientalism', and Popular Culture. Lau, Jenny Kwok Wah (编). Multiple Modernities: Cinemas and Popular Media in Transcultural East Asia. Temple University Press. 2003: 53–75 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-1-56639-986-9. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

网页

- AFP staff. Print by Japan's Toshusai Sharaku sold for record price. AFP. 2009-10-16 [2013-12-07]. (原始内容存档于2014-03-03).

- Fiorillo, John. Kindai Hanga. Viewing Japanese Prints. [2013-12-07]. (原始内容存档于2013-12-08).

- Fiorillo, John. FAQ: Care and Repair of Japanese Prints. Viewing Japanese Prints. [2013-12-17]. (原始内容存档于2014-11-04).

- Fiorillo, John. FAQ: "Original" Prints. Viewing Japanese Prints. [2013-12-17]. (原始内容存档于2013-06-24).

- Fiorillo, John. FAQ: How do you grade quality and condition?. Viewing Japanese Prints. [2013-12-17]. (原始内容存档于2012-11-03).

- Fiorillo, John. Deceptive Copies (Takamizawa Enji). Viewing Japanese Prints. [2013-12-17]. (原始内容存档于2013-12-07).

扩展阅读

- Calza, Gian Carlo. Ukiyo-E. Phaidon Press. 2007. ISBN 978-0-7148-4794-8.

- Kanada, Margaret Miller. Color Woodblock Printmaking: The Traditional Method of Ukiyo-e. Shufunomoto. 1989 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-4-07-975316-6. (原始内容存档于2017-03-24).

- Lane, Richard. Images from the Floating World, The Japanese Print. Oxford University Press. 1978. ISBN 978-0-19-211447-1.

- Newland, Amy Reigle. Hotei Encyclopedia of Japanese Woodblock Prints. Hotei. 2005. ISBN 978-90-74822-65-7.

- Stewart, Basil. A Guide to Japanese Prints and Their Subject Matter. Courier Dover Publications. 1922 [2014-08-04]. ISBN 978-0-48-623809-8. (原始内容存档于2021-04-17).

外部链接

- Beauty Looking Back, Moronobu, late 17th century

- Shibai Uki-e, Masanobu, c. 1741–1744

- Otani Oniji III, Sharaku, 1794

- Comb, Utamaro, 1798

- Hara, 13th station of The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, Hiroshige, 1833–34

- Cuckoo and Azaleas, Hokusai, 1828

- Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre, Kuniyoshi, c. 1844

Ukiyo-e[a] (浮世絵) is a genre of Japanese art that flourished from the 17th through 19th centuries. Its artists produced woodblock prints and paintings of such subjects as female beauties; kabuki actors and sumo wrestlers; scenes from history and folk tales; travel scenes and landscapes; flora and fauna; and erotica. The term ukiyo-e (浮世絵) translates as "picture[s] of the floating world".

In 1603, the city of Edo (Tokyo) became the seat of the ruling Tokugawa shogunate. The chōnin class (merchants, craftsmen and workers), positioned at the bottom of the social order, benefited the most from the city's rapid economic growth. They began to indulge in and patronize the entertainment of kabuki theatre, geisha, and courtesans of the pleasure districts. The term ukiyo ('floating world') came to describe this hedonistic lifestyle. Printed or painted ukiyo-e works were popular with the chōnin class, who had become wealthy enough to afford to decorate their homes with them.

The earliest ukiyo-e works emerged in the 1670s, with Hishikawa Moronobu's paintings and monochromatic prints of beautiful women. Colour prints were introduced gradually, and at first were only used for special commissions. By the 1740s, artists such as Okumura Masanobu used multiple woodblocks to print areas of colour. In the 1760s, the success of Suzuki Harunobu's "brocade prints" led to full-colour production becoming standard, with ten or more blocks used to create each print. Some ukiyo-e artists specialized in making paintings, but most works were prints. Artists rarely carved their own woodblocks for printing; rather, production was divided between the artist, who designed the prints; the carver, who cut the woodblocks; the printer, who inked and pressed the woodblocks onto handmade paper; and the publisher, who financed, promoted, and distributed the works. As printing was done by hand, printers were able to achieve effects impractical with machines, such as the blending or gradation of colours on the printing block.

Specialists have prized the portraits of beauties and actors by masters such as Torii Kiyonaga, Utamaro, and Sharaku that were created in the late 18th century. The 19th century also saw the continuation of masters of the ukiyo-e tradition, with the creation of Hokusai's The Great Wave off Kanagawa, one of the most well-known works of Japanese art, and Hiroshige's The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō. Following the deaths of these two masters, and against the technological and social modernization that followed the Meiji Restoration of 1868, ukiyo-e production went into steep decline.

However, in the 20th century there was a revival in Japanese printmaking: the shin-hanga ('new prints') genre capitalized on Western interest in prints of traditional Japanese scenes, and the sōsaku-hanga ('creative prints') movement promoted individualist works designed, carved, and printed by a single artist. Prints since the late 20th century have continued in an individualist vein, often made with techniques imported from the West.

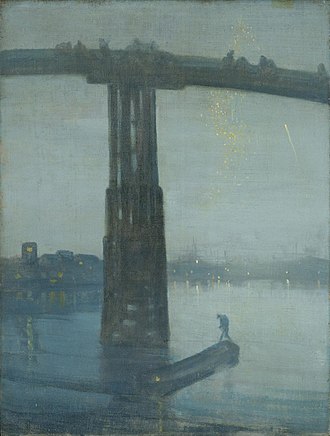

Ukiyo-e was central to forming the West's perception of Japanese art in the late 19th century, particularly the landscapes of Hokusai and Hiroshige. From the 1870s onward, Japonisme became a prominent trend and had a strong influence on the early French Impressionists such as Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet and Claude Monet, as well as influencing Post-Impressionists such as Vincent van Gogh, and Art Nouveau artists such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

History

Early history

Japanese art since the Heian period (794–1185) had followed two principal paths: the nativist Yamato-e tradition, focusing on Japanese themes, best known by the works of the Tosa school; and Chinese-inspired kara-e in a variety of styles, such as the monochromatic ink wash paintings of Sesshū Tōyō and his disciples. The Kanō school of painting incorporated features of both.[1]

Since antiquity, Japanese art had found patrons in the aristocracy, military governments, and religious authorities.[2] Until the 16th century, the lives of the common people had not been a main subject of painting, and even when they were included, the works were luxury items made for the ruling samurai and rich merchant classes.[3] Later works appeared by and for townspeople, including inexpensive monochromatic paintings of female beauties and scenes of the theatre and pleasure districts. The hand-produced nature of these shikomi-e (仕込絵) limited the scale of their production, a limit that was soon overcome by genres that turned to mass-produced woodblock printing.[4]

During a prolonged period of civil war in the 16th century, a class of politically powerful merchants developed. These machishū, the predecessors of the Edo period's chōnin, allied themselves with the court and had power over local communities; their patronage of the arts encouraged a revival in the classical arts in the late 16th and early 17th centuries.[5] In the early 17th century, Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616) unified the country and was appointed shōgun with supreme power over Japan. He consolidated his government in the village of Edo (modern Tokyo),[6] and required the territorial lords to assemble there in alternate years with their entourages. The demands of the growing capital drew many male labourers from the country, so that males came to make up nearly seventy percent of the population.[7] The village grew during the Edo period (1603–1867) from a population of 1800 to over a million in the 19th century.[6]

The centralized shogunate put an end to the power of the machishū and divided the population into four social classes, with the ruling samurai class at the top and the merchant class at the bottom. While deprived of their political influence,[5] those of the merchant class most benefited from the rapidly expanding economy of the Edo period,[8] and their improved lot allowed for leisure that many sought in the pleasure districts—in particular Yoshiwara in Edo[6]—and collecting artworks to decorate their homes, which in earlier times had been well beyond their financial means.[9] The experience of the pleasure quarters was open to those of sufficient wealth, manners, and education.[10]

Woodblock printing in Japan traces back to the Hyakumantō Darani in 770 CE. Until the 17th century, such printing was reserved for Buddhist seals and images.[11] Movable type appeared around 1600, but as the Japanese writing system required about 100,000 type pieces,[b] hand-carving text onto woodblocks was more efficient. In Saga, Kyoto, calligrapher Hon'ami Kōetsu and publisher Suminokura Soan combined printed text and images in an adaptation of The Tales of Ise (1608) and other works of literature.[12] During the Kan'ei era (1624–1643) illustrated books of folk tales called tanrokubon ('orange-green books') were the first books mass-produced using woodblock printing.[11] Woodblock imagery continued to evolve as illustrations to the kanazōshi genre of tales of hedonistic urban life in the new capital.[13] The rebuilding of Edo following the Great Fire of Meireki in 1657 occasioned a modernization of the city, and the publication of illustrated printed books flourished in the rapidly urbanizing environment.[14]

The term ukiyo (浮世), which can be translated as 'floating world', was homophonous with the ancient Buddhist term ukiyo (憂き世), meaning 'this world of sorrow and grief'. The newer term at times was used to mean 'erotic' or 'stylish', among other meanings, and came to describe the hedonistic spirit of the time for the lower classes. Asai Ryōi celebrated this spirit in the novel Ukiyo Monogatari (Tales of the Floating World, c. 1661):[15]

[L]iving only for the moment, savouring the moon, the snow, the cherry blossoms, and the maple leaves, singing songs, drinking sake, and diverting oneself just in floating, unconcerned by the prospect of imminent poverty, buoyant and carefree, like a gourd carried along with the river current: this is what we call ukiyo.

Emergence of ukiyo-e (late 17th – early 18th centuries)

The earliest ukiyo-e artists came from the world of Japanese painting.[16] Yamato-e painting of the 17th century had developed a style of outlined forms which allowed inks to be dripped on a wet surface and spread out towards the outlines—this outlining of forms was to become the dominant style of ukiyo-e.[17]

Around 1661, painted hanging scrolls known as Portraits of Kanbun Beauties gained popularity. The paintings of the Kanbun era (1661–1673), most of which are anonymous, marked the beginnings of ukiyo-e as an independent school.[16] The paintings of Iwasa Matabei (1578–1650) have a great affinity with ukiyo-e paintings. Scholars disagree whether Matabei's work itself is ukiyo-e;[18] assertions that he was the genre's founder are especially common amongst Japanese researchers.[19] At times Matabei has been credited as the artist of the unsigned Hikone screen,[20] a byōbu folding screen that may be one of the earliest surviving ukiyo-e works. The screen is in a refined Kanō style and depicts contemporary life, rather than the prescribed subjects of the painterly schools.[21]

In response to the increasing demand for ukiyo-e works, Hishikawa Moronobu (1618–1694) produced the first ukiyo-e woodblock prints.[16] By 1672, Moronobu's success was such that he began to sign his work—the first of the book illustrators to do so. He was a prolific illustrator who worked in a wide variety of genres, and developed an influential style of portraying female beauties. Most significantly, he began to produce illustrations, not just for books, but as single-sheet images, which could stand alone or be used as part of a series. The Hishikawa school attracted a large number of followers,[22] as well as imitators such as Sugimura Jihei,[23] and signalled the beginning of the popularization of a new artform.[24]

Torii Kiyonobu I and Kaigetsudō Ando became prominent emulators of Moronobu's style following the master's death, though neither was a member of the Hishikawa school. Both discarded background detail in favour of focus on the human figure—kabuki actors in the yakusha-e of Kiyonobu and the Torii school that followed him,[25] and courtesans in the bijin-ga of Ando and his Kaigetsudō school. Ando and his followers produced a stereotyped female image whose design and pose lent itself to effective mass production,[26] and its popularity created a demand for paintings that other artists and schools took advantage of.[27] The Kaigetsudō school and its popular "Kaigetsudō beauty" ended after Ando's exile over his role in the Ejima-Ikushima scandal of 1714.[28]

Kyoto native Nishikawa Sukenobu (1671–1750) painted technically refined pictures of courtesans.[29] Considered a master of erotic portraits, he was the subject of a government ban in 1722, though it is believed he continued to create works that circulated under different names.[30] Sukenobu spent most of his career in Edo, and his influence was considerable in both the Kantō and Kansai regions.[29] The paintings of Miyagawa Chōshun (1683–1752) portrayed early 18th-century life in delicate colours. Chōshun made no prints.[31] The Miyagawa school he founded in the early-18th century specialized in romantic paintings in a style more refined in line and colour than the Kaigetsudō school. Chōshun allowed greater expressive freedom in his adherents, a group that later included Hokusai.[27]

- Early ukiyo-e masters

-

Standing portrait of a courtesanInk and colour painting on silk, Kaigetsudō Ando, c. 1705–10

-

Portrait of actorsHand-coloured printKiyonobu, 1714

-

Printed page from Asakayama E-honSukenobu, 1739

-

Ryukyuan Dancer and MusiciansInk and color painting on silk, Chōshun, c. 1718

Colour prints (mid-18th century)

Even in the earliest monochromatic prints and books, colour was added by hand for special commissions. Demand for colour in the early-18th century was met with tan-e[c] prints hand-tinted with orange and sometimes green or yellow.[33] These were followed in the 1720s with a vogue for pink-tinted beni-e[d] and later the lacquer-like ink of the urushi-e. In 1744, the benizuri-e were the first successes in colour printing, using multiple woodblocks—one for each colour, the earliest beni pink and vegetable green.[34]

A great self-promoter, Okumura Masanobu (1686–1764) played a major role during the period of rapid technical development in printing from the late 17th to mid-18th centuries.[34] He established a shop in 1707[35] and combined elements of the leading contemporary schools in a wide array of genres, though Masanobu himself belonged to no school. Amongst the innovations in his romantic, lyrical images were the introduction of geometrical perspective in the uki-e genre[e] in the 1740s;[39] the long, narrow hashira-e prints; and the combination of graphics and literature in prints that included self-penned haiku poetry.[40]

Ukiyo-e reached a peak in the late 18th century with the advent of full-colour prints, developed after Edo returned to prosperity under Tanuma Okitsugu following a long depression.[41] These popular colour prints came to be called nishiki-e, or 'brocade pictures', as their brilliant colours seemed to bear resemblance to imported Chinese Shuchiang brocades, known in Japanese as Shokkō nishiki.[42] The first to emerge were expensive calendar prints, printed with multiple blocks on very fine (or finer than standard) paper with heavy, opaque inks. These prints had the number of days for each month hidden in the design, and were sent at the New Year[f] as personalized greetings, bearing the name of the patron rather than the artist. The blocks for these prints were later re-used for commercial production, obliterating the patron's name and replacing it with that of the artist.[43]

The delicate, romantic prints of Suzuki Harunobu (1725–1770) were amongst the first to realize expressive and complex colour designs,[44] printed with up to a dozen separate blocks to handle the different colours[45] and half-tones.[46] His restrained, graceful prints invoked the classicism of waka poetry and Yamato-e painting. The prolific Harunobu was the dominant ukiyo-e artist of his time.[47] The success of Harunobu's colourful nishiki-e from 1765 on led to a steep decline in demand for the limited palettes of benizuri-e and urushi-e, as well as hand-coloured prints.[45]

A trend against the idealism of the prints of Harunobu and the Torii school grew following Harunobu's death in 1770. Katsukawa Shunshō (1726–1793) and his school produced portraits of kabuki actors with greater fidelity to the actors' actual features than had been the trend.[48] Sometime-collaborators Koryūsai (1735 – c. 1790) and Kitao Shigemasa (1739–1820) were prominent depicters of women who also moved ukiyo-e away from the dominance of Harunobu's idealism by focusing on contemporary urban fashions and celebrated real-world courtesans and geisha.[49] Koryūsai was perhaps the most prolific ukiyo-e artist of the 18th century, and produced a larger number of paintings and print series than any predecessor.[50] The Kitao school that Shigemasa founded was one of the dominant schools of the closing decades of the 18th century.[51]

In the 1770s, Utagawa Toyoharu produced a number of uki-e perspective prints[52] that demonstrated a mastery of Western perspective techniques that had eluded his predecessors in the genre.[36] Toyoharu's works helped pioneer the landscape as an ukiyo-e subject, rather than merely a background for human figures.[53] In the 19th century, Western-style perspective techniques were absorbed into Japanese artistic culture, and deployed in the refined landscapes of such artists as Hokusai and Hiroshige,[54] the latter a member of the Utagawa school that Toyoharu founded. This school was to become one of the most influential,[55] and produced works in a far greater variety of genres than any other school.[56]

- Early colour ukiyo-e

-

Two Lovers Beneath an Umbrella in the SnowHarunobu, c. 1767

-

Arashi Otohachi as Ippon SaemonShunshō, 1768

-

Hinazuru of the ChōjiyaKoryūsai, c. 1778–80

-

Geisha and a servant carrying her shamisen boxShigemasa, 1777

Peak period (late 18th century)

While the late 18th century saw hard economic times,[57] ukiyo-e saw a peak in quantity and quality of works, particularly during the Kansei era (1789–1791).[58] The ukiyo-e of the period of the Kansei Reforms brought about a focus on beauty and harmony[51] that collapsed into decadence and disharmony in the next century as the reforms broke down and tensions rose, culminating in the Meiji Restoration of 1868.[58]

Especially in the 1780s, Torii Kiyonaga (1752–1815)[51] of the Torii school[58] depicted traditional ukiyo-e subjects like beauties and urban scenes, which he printed on large sheets of paper, often as multiprint horizontal diptychs or triptychs. His works dispensed with the poetic dreamscapes made by Harunobu, opting instead for realistic depictions of idealized female forms dressed in the latest fashions and posed in scenic locations.[59] He also produced portraits of kabuki actors in a realistic style that included accompanying musicians and chorus.[60]

A law went into effect in 1790 requiring prints to bear a censor's seal of approval to be sold. Censorship increased in strictness over the following decades, and violators could receive harsh punishments. From 1799 even preliminary drafts required approval.[61] A group of Utagawa-school offenders including Toyokuni had their works repressed in 1801, and Utamaro was imprisoned in 1804 for making prints of 16th-century political and military leader Toyotomi Hideyoshi.[62]

Utamaro (c. 1753–1806) made his name in the 1790s with his bijin ōkubi-e ('large-headed pictures of beautiful women') portraits, focusing on the head and upper torso, a style others had previously employed in portraits of kabuki actors.[63] Utamaro experimented with line, colour, and printing techniques to bring out subtle differences in the features, expressions, and backdrops of subjects from a wide variety of class and background. Utamaro's individuated beauties were in sharp contrast to the stereotyped, idealized images that had been the norm.[64] By the end of the decade, especially following the death of his patron Tsutaya Jūzaburō in 1797, Utamaro's prodigious output declined in quality,[65] and he died in 1806.[66]

Appearing suddenly in 1794 and disappearing just as suddenly ten months later, the prints of the enigmatic Sharaku are amongst ukiyo-e's best known. Sharaku produced striking portraits of kabuki actors, introducing a greater level of realism into his prints that emphasized the differences between the actor and the portrayed character.[67] The expressive, contorted faces he depicted contrasted sharply with the serene, mask-like faces more common to artists such as Harunobu or Utamaro.[46] Published by Tsutaya,[66] Sharaku's work found resistance, and in 1795 his output ceased as mysteriously as it had appeared; his real identity is still unknown.[68] Utagawa Toyokuni (1769–1825) produced kabuki portraits in a style Edo townsfolk found more accessible, emphasizing dramatic postures and avoiding Sharaku's realism.[67]

A consistent high level of quality marks ukiyo-e of the late 18th-century, but the works of Utamaro and Sharaku often overshadow those other masters of the era.[66] One of Kiyonaga's followers,[58] Eishi (1756–1829), abandoned his position as painter for shōgun Tokugawa Ieharu to take up ukiyo-e design. He brought a refined sense to his portraits of graceful, slender courtesans, and left behind a number of noted students.[66] With a fine line, Eishōsai Chōki (fl. 1786–1808) designed portraits of delicate courtesans. The Utagawa school came to dominate ukiyo-e output in the late Edo period.[69]

Edo was the primary centre of ukiyo-e production throughout the Edo period. Another major centre developed in the Kamigata region of areas in and around Kyoto and Osaka. In contrast to the range of subjects in the Edo prints, those of Kamigata tended to be portraits of kabuki actors. The style of the Kamigata prints was little distinguished from those of Edo until the late 18th century, partly because artists often moved back and forth between the two areas.[70] Colours tend to be softer and pigments thicker in Kamigata prints than in those of Edo.[71] In the 19th century, many of the prints were designed by kabuki fans and other amateurs.[72]

- Masters of the peak period

-

Cooling on RiversideKiyonaga, c. 1785

-

Ichikawa Ebizo as Takemura SadanoshinSharaku, 1794

-

Onoe Eisaburo IToyokuni, c. 1800

-

Niwaka Festival in the Licensed QuartersChōki, c. 1800

Late flowering: flora, fauna, and landscapes (19th century)

The Tenpō Reforms of 1841–1843 sought to suppress outward displays of luxury, including the depiction of courtesans and actors. As a result, many ukiyo-e artists designed travel scenes and pictures of nature, especially birds and flowers.[73] Landscapes had been given limited attention since Moronobu, and they formed an important element in the works of Kiyonaga and Shunchō. It was not until late in the Edo period that landscape came into its own as a genre, especially via the works of Hokusai and Hiroshige The landscape genre has come to dominate Western perceptions of ukiyo-e, though ukiyo-e had a long history preceding these late-era masters.[74] The Japanese landscape differed from the Western tradition in that it relied more heavily on imagination, composition, and atmosphere than on strict observance of nature.[75]

The self-proclaimed "mad painter" Hokusai (1760–1849) enjoyed a long, varied career. His work is marked by a lack of the sentimentality common to ukiyo-e, and a focus on formalism influenced by Western art. Among his accomplishments are his illustrations of Takizawa Bakin's novel Crescent Moon, his series of sketchbooks, the Hokusai Manga, and his popularization of the landscape genre with Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji,[76] which includes his best-known print, The Great Wave off Kanagawa,[77] one of the most famous works of Japanese art.[78] In contrast to the work of the older masters, Hokusai's colours were bold, flat, and abstract, and his subject was not the pleasure districts but the lives and environment of the common people at work.[79] Established masters Eisen, Kuniyoshi, and Kunisada also followed Hokusai's steps into landscape prints in the 1830s, producing prints with bold compositions and striking effects.[80]

Though not often given the attention of their better-known forebears, the Utagawa school produced a few masters in this declining period. The prolific Kunisada (1786–1865) had few rivals in the tradition of making portrait prints of courtesans and actors.[81] One of those rivals was Eisen (1790–1848), who was also adept at landscapes.[82] Perhaps the last significant member of this late period, Kuniyoshi (1797–1861) tried his hand at a variety of themes and styles, much as Hokusai had. His historical scenes of warriors in violent combat were popular,[83] especially his series of heroes from the Suikoden (1827–1830) and Chūshingura (1847).[84] He was adept at landscapes and satirical scenes—the latter an area rarely explored in the dictatorial atmosphere of the Edo period; that Kuniyoshia could dare tackle such subjects was a sign of the weakening of the shogunate at the time.[83]

Hiroshige (1797–1858) is considered Hokusai's greatest rival in stature. He specialized in pictures of birds and flowers, and serene landscapes, and is best known for his travel series, such as The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō and The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kisokaidō,[85] the latter a cooperative effort with Eisen.[82] His work was more realistic, subtly coloured, and atmospheric than Hokusai's; nature and the seasons were key elements: mist, rain, snow, and moonlight were prominent parts of his compositions.[86] Hiroshige's followers, including adopted son Hiroshige II and son-in-law Hiroshige III, carried on their master's style of landscapes into the Meiji era.[87]

- Masters of the late period

-

Dawn at Futami-ga-uraKunisada, c. 1832

-

Two mandarin ducksHiroshige, 1838

Decline (late 19th century)

Following the deaths of Hokusai and Hiroshige[88] and the Meiji Restoration of 1868, ukiyo-e suffered a sharp decline in quantity and quality.[89] The rapid Westernization of the Meiji period that followed saw woodblock printing turn its services to journalism, and face competition from photography. Practitioners of pure ukiyo-e became more rare, and tastes turned away from a genre seen as a remnant of an obsolescent era.[88] Artists continued to produce occasional notable works, but by the 1890s the tradition was moribund.[90]

Synthetic pigments imported from Germany began to replace traditional organic ones in the mid-19th century. Many prints from this era made extensive use of a bright red, and were called aka-e ('red pictures').[91] Artists such as Yoshitoshi (1839–1892) led a trend in the 1860s of gruesome scenes of murders and ghosts,[92] monsters and supernatural beings, and legendary Japanese and Chinese heroes. His One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (1885–1892) depicts a variety of fantastic and mundane themes with a moon motif.[93] Kiyochika (1847–1915) is known for his prints documenting the rapid modernization of Tokyo, such as the introduction of railways, and his depictions of Japan's wars with China and with Russia.[92] Earlier a painter of the Kanō school, in the 1870s Chikanobu (1838–1912) turned to prints, particularly of the imperial family and scenes of Western influence on Japanese life in the Meiji period.[94]

- Meiji-era ukiyo-e

-

Mirror of the Japanese NobilityChikanobu, 1887

-

From One Hundred Aspects of the MoonYoshitoshi, 1891

-

Russo-Japanese Naval Battle at the Entrance of Incheon: The Great Victory of the Japanese Navy—Banzai!Kiyochika, 1904

Introduction to the West

Aside from Dutch traders, who had had trading relations dating to the beginning of the Edo period,[95] Westerners paid little notice to Japanese art before the mid-19th century, and when they did they rarely distinguished it from other art from the East.[95] Swedish naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg spent a year in the Dutch trading settlement Dejima, near Nagasaki, and was one of the earliest Westerners to collect Japanese prints. The export of ukiyo-e thereafter slowly grew, and at the beginning of the 19th century Dutch merchant-trader Isaac Titsingh's collection drew the attention of connoisseurs of art in Paris.[96]

The arrival in Edo of American Commodore Matthew Perry in 1853 led to the Convention of Kanagawa in 1854, which opened Japan to the outside world after over two centuries of seclusion. Ukiyo-e prints were amongst the items he brought back to the United States.[97] Such prints had appeared in Paris from at least the 1830s, and by the 1850s were numerous;[98] reception was mixed, and even when praised ukiyo-e was generally thought inferior to Western works which emphasized mastery of naturalistic perspective and anatomy.[99] Japanese art drew notice at the International Exhibition of 1867 in Paris,[95] and became fashionable in France and England in the 1870s and 1880s.[95] The prints of Hokusai and Hiroshige played a prominent role in shaping Western perceptions of Japanese art.[100] At the time of their introduction to the West, woodblock printing was the most common mass medium in Japan, and the Japanese considered it of little lasting value.[101]

Early Europeans promoters and scholars of ukiyo-e and Japanese art included writer Edmond de Goncourt and art critic Philippe Burty,[102] who coined the term Japonism.[103][g] Stores selling Japanese goods opened, including those of Édouard Desoye in 1862 and art dealer Siegfried Bing in 1875.[104] From 1888 to 1891 Bing published the magazine Artistic Japan[105] in English, French, and German editions,[106] and curated an ukiyo-e exhibition at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1890 attended by artists such as Mary Cassatt.[107]

American Ernest Fenollosa was the earliest Western devotee of Japanese culture, and did much to promote Japanese art—Hokusai's works featured prominently at his inaugural exhibition as first curator of Japanese art Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and in Tokyo in 1898 he curated the first ukiyo-e exhibition in Japan.[108] By the end of the 19th century, the popularity of ukiyo-e in the West drove prices beyond the means of most collectors—some, such as Degas, traded their own paintings for such prints. Tadamasa Hayashi was a prominent Paris-based dealer of respected tastes whose Tokyo office was responsible for evaluating and exporting large quantities of ukiyo-e prints to the West in such quantities that Japanese critics later accused him of siphoning Japan of its national treasure.[109] The drain first went unnoticed in Japan, as Japanese artists were immersing themselves in the classical painting techniques of the West.[110]

Japanese art, and particularly ukiyo-e prints, came to influence Western art from the time of the early Impressionists.[111] Early painter-collectors incorporated Japanese themes and compositional techniques into their works as early as the 1860s:[98] the patterned wallpapers and rugs in Manet's paintings were inspired by the patterned kimono found in ukiyo-e pictures, and Whistler focused his attention on ephemeral elements of nature as in ukiyo-e landscapes.[112] Van Gogh was an avid collector, and painted copies in oil of prints by Hiroshige and Eisen.[113] Degas and Cassatt depicted fleeting, everyday moments in Japanese-influenced compositions and perspectives.[114] ukiyo-e's flat perspective and unmodulated colours were a particular influence on graphic designers and poster makers.[115] Toulouse-Lautrec's lithographs displayed his interest not only in ukiyo-e's flat colours and outlined forms, but also in their subject matter: performers and prostitutes.[116] He signed much of this work with his initials in a circle, imitating the seals on Japanese prints.[116] Other artists of the time who drew influence from ukiyo-e include Monet,[111] La Farge,[117] Gauguin,[118] and Les Nabis members such as Bonnard[119] and Vuillard.[120] French composer Claude Debussy drew inspiration for his music from the prints of Hokusai and Hiroshige, most prominently in La mer (1905).[121] Imagist poets such as Amy Lowell and Ezra Pound found inspiration in ukiyo-e prints; Lowell published a book of poetry called Pictures of the Floating World (1919) on oriental themes or in an oriental style.[122]

- Ukiyo-e influence on Western art

-

Bamboo Yards, Kyōbashi BridgeHiroshige, c. 1857–58

-

Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi bridge and AtakeHiroshige, 1857

-

Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Paintings GalleryDegas, c. 1879–80

-

Woman BathingCassatt, c. 1890–91

Descendant traditions (20th century)

The travel sketchbook became a popular genre beginning about 1905, as the Meiji government promoted travel within Japan to have citizens better know their country.[123] In 1915, publisher Shōzaburō Watanabe introduced the term shin-hanga ("new prints") to describe a style of prints he published that featured traditional Japanese subject matter and were aimed at foreign and upscale Japanese audiences.[124] Prominent artists included Goyō Hashiguchi, called the "Utamaro of the Taishō period" for his manner of depicting women; Shinsui Itō, who brought more modern sensibilities to images of women;[125] and Hasui Kawase, who made modern landscapes.[126] Watanabe also published works by non-Japanese artists, an early success of which was a set of Indian- and Japanese-themed prints in 1916 by the English Charles W. Bartlett (1860–1940). Other publishers followed Watanabe's success, and some shin-hanga artists such as Goyō and Hiroshi Yoshida set up studios to publish their own work.[127]

Artists of the sōsaku-hanga ('creative prints') movement took control of every aspect of the printmaking process—design, carving, and printing were by the same pair of hands.[124] Kanae Yamamoto (1882–1946), then a student at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, is credited with the birth of this approach. In 1904, he produced Fisherman using woodblock printing, a technique until then frowned upon by the Japanese art establishment as old-fashioned and for its association with commercial mass production.[128] The foundation of the Japanese Woodcut Artists' Association in 1918 marks the beginning of this approach as a movement.[129] The movement favoured individuality in its artists, and as such has no dominant themes or styles.[130] Works ranged from the entirely abstract ones of Kōshirō Onchi (1891–1955) to the traditional figurative depictions of Japanese scenes of Un'ichi Hiratsuka (1895–1997).[129] These artists produced prints not because they hoped to reach a mass audience, but as a creative end in itself, and did not restrict their print media to the woodblock of traditional ukiyo-e.[131]

Prints from the late-20th and 21st centuries have evolved from the concerns of earlier movements, especially the sōsaku-hanga movement's emphasis on individual expression. Screen printing, etching, mezzotint, mixed media, and other Western methods have joined traditional woodcutting amongst printmakers' techniques.[132]

- Descendants of ukiyo-e

-

Taj Mahal, Charles W. Bartlett, 1916

-

Combing the HairGoyō Hashiguchi, 1920

-

Shiba Zōjōji, Hasui Kawase, 1925

-

Glittering Sea, by Hiroshi Yoshida, 1926

-

Lyric No. 23Kōshirō Onchi, 1952

Style

Early ukiyo-e artists brought with them a sophisticated knowledge of and training in the composition principles of classical Chinese painting; gradually these artists shed the overt Chinese influence to develop a native Japanese idiom. The early ukiyo-e artists have been called "Primitives" in the sense that the print medium was a new challenge to which they adapted these centuries-old techniques—their image designs are not considered "primitive".[133] Many ukiyo-e artists received training from teachers of the Kanō and other painterly schools.[134]

A defining feature of most ukiyo-e prints is a well-defined, bold, flat line.[135] The earliest prints were monochromatic, and these lines were the only printed element; even with the advent of colour this characteristic line continued to dominate.[136] In ukiyo-e composition forms are arranged in flat spaces[137] with figures typically in a single plane of depth. Attention was drawn to vertical and horizontal relationships, as well as details such as lines, shapes, and patterns such as those on clothing.[138] Compositions were often asymmetrical, and the viewpoint was often from unusual angles, such as from above. Elements of images were often cropped, giving the composition a spontaneous feel.[139] In colour prints, contours of most colour areas are sharply defined, usually by the linework.[140] The aesthetic of flat areas of colour contrasts with the modulated colours expected in Western traditions[137] and with other prominent contemporary traditions in Japanese art patronized by the upper class, such as in the subtle monochrome ink brushstrokes of zenga brush painting or tonal colours of the Kanō school of painting.[140]

The colourful, ostentatious, and complex patterns, concern with changing fashions, and tense, dynamic poses and compositions in ukiyo-e are in striking contrast with many concepts in traditional Japanese aesthetics. Prominent amongst these, wabi-sabi favours simplicity, asymmetry, and imperfection, with evidence of the passage of time;[141] and shibui values subtlety, humility, and restraint.[142] Ukiyo-e can be less at odds with aesthetic concepts such as the racy, urbane stylishness of iki.[143]

Ukiyo-e displays an unusual approach to graphical perspective, one that can appear underdeveloped when compared to European paintings of the same period. Western-style geometrical perspective was known in Japan—practised most prominently by the Akita ranga painters of the 1770s—as were Chinese methods to create a sense of depth using a homogeny of parallel lines. The techniques sometimes appeared together in ukiyo-e works, geometrical perspective providing an illusion of depth in the background and the more expressive Chinese perspective in the fore.[144] The techniques were most likely learned at first through Chinese Western-style paintings rather than directly from Western works.[145] Long after becoming familiar with these techniques, artists continued to harmonize them with traditional methods according to their compositional and expressive needs.[146] Other ways of indicating depth included the Chinese tripartite composition method used in Buddhist pictures, where a large form is placed in the foreground, a smaller in the midground, and yet a smaller in the background; this can be seen in Hokusai's Great Wave, with a large boat in the foreground, a smaller behind it, and a small Mt Fuji behind them.[147]

There was a tendency since early ukiyo-e to pose beauties in what art historian Midori Wakakura called a "serpentine posture",[h] which involves the subjects' bodies twisting unnaturally while facing behind themselves. Art historian Motoaki Kōno posited that this had its roots in traditional buyō dance; Haruo Suwa countered that the poses were artistic licence taken by ukiyo-e artists, causing a seemingly relaxed pose to reach unnatural or impossible physical extremes. This remained the case even when realistic perspective techniques were applied to other sections of the composition.[148]

Themes and genres

Typical subjects were female beauties ("bijin-ga"), kabuki actors ("yakusha-e"), and landscapes. The women depicted were most often courtesans and geisha at leisure, and promoted the entertainments to be found in the pleasure districts.[149] The detail with which artists depicted courtesans' fashions and hairstyles allows the prints to be dated with some reliability. Less attention was given to accuracy of the women's physical features, which followed the day's pictorial fashions—the faces stereotyped, the bodies tall and lanky in one generation and petite in another.[150] Portraits of celebrities were much in demand, in particular those from the kabuki and sumo worlds, two of the most popular entertainments of the era.[151] While the landscape has come to define ukiyo-e for many Westerners, landscapes flourished relatively late in the ukiyo-e's history.[74]

Ukiyo-e prints grew out of book illustration—many of Moronobu's earliest single-page prints were originally pages from books he had illustrated.[12] E-hon books of illustrations were popular[152] and continued be an important outlet for ukiyo-e artists. In the late period, Hokusai produced the three-volume One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji and the 15-volume Hokusai Manga, the latter a compendium of over 4000 sketches of a wide variety of realistic and fantastic subjects.[153]

Traditional Japanese religions do not consider sex or pornography a moral corruption in the sense of most Abrahamic faiths,[154] and until the changing morals of the Meiji era led to its suppression, shunga erotic prints were a major genre.[155] While the Tokugawa regime subjected Japan to strict censorship laws, pornography was not considered an important offence and generally met with the censors' approval.[62] Many of these prints displayed a high level a draughtsmanship, and often humour, in their explicit depictions of bedroom scenes, voyeurs, and oversized anatomy.[156] As with depictions of courtesans, these images were closely tied to entertainments of the pleasure quarters.[157] Nearly every ukiyo-e master produced shunga at some point.[158] Records of societal acceptance of shunga are absent, though Timon Screech posits that there were almost certainly some concerns over the matter, and that its level of acceptability has been exaggerated by later collectors, especially in the West.[157]

Scenes from nature have been an important part of Asian art throughout history. Artists have closely studied the correct forms and anatomy of plants and animals, even though depictions of human anatomy remained more fanciful until modern times. Ukiyo-e nature prints are called kachō-e, which translates as "flower-and-bird pictures", though the genre was open to more than just flowers or birds, and the flowers and birds did not necessarily appear together.[73] Hokusai's detailed, precise nature prints are credited with establishing kachō-e as a genre.[159]

The Tenpō Reforms of the 1840s suppressed the depiction of actors and courtesans. Aside from landscapes and kachō-e, artists turned to depictions of historical scenes, such as of ancient warriors or of scenes from legend, literature, and religion. The 11th century Tale of Genji[160] and the 13th-century Tale of the Heike[161] have been sources of artistic inspiration throughout Japanese history,[160] including in ukiyo-e.[160] Well-known warriors and swordsmen such as Miyamoto Musashi (1584–1645) were frequent subjects, as were depictions of monsters, the supernatural, and heroes of Japanese and Chinese mythology.[162]

From the 17th to 19th centuries, Japan isolated itself from the rest of the world. Trade, primarily with the Dutch and Chinese, was restricted to the island of Dejima near Nagasaki. Outlandish pictures called Nagasaki-e were sold to tourists of the foreigners and their wares.[97] In the mid-19th century, Yokohama became the primary foreign settlement after 1859, from which Western knowledge proliferated in Japan.[163] Especially from 1858 to 1862, Yokohama-e prints documented, with various levels of fact and fancy, the growing community of world denizens with whom the Japanese were now coming in contact;[164] triptychs of scenes of Westerners and their technology were particularly popular.[165]

Specialized prints included surimono, deluxe, limited-edition prints aimed at connoisseurs, of which a five-line kyōka poem was usually part of the design;[166] and uchiwa-e printed hand fans, which often suffer from having been handled.[12]

- Ukiyo-e genres

-

English CoupleYokohama-e by Utagawa Yoshitora, 1860

Production

Paintings

Ukiyo-e artists often made both prints and paintings; some specialized in one or the other.[167] In contrast with previous traditions, ukiyo-e painters favoured bright, sharp colours,[168] and often delineated contours with sumi ink, an effect similar to the linework in prints.[169] Unrestricted by the technical limitations of printing, a wider range of techniques, pigments, and surfaces were available to the painter.[170] Artists painted with pigments made from mineral or organic substances, such as safflower, ground shells, lead, and cinnabar,[171] and later synthetic dyes imported from the West such as Paris green and Prussian blue.[172] Silk or paper kakemono hanging scrolls, makimono handscrolls, or byōbu folding screens were the most common surfaces.[167]

- Ukiyo-e paintings

-

Bijin-gaKaigetsudō Ando, 18th century

-

A Winter PartyUtagawa Toyoharu, mid-18th – late 19th century

-

Yoshiwara no HanaUtamaro, c. 1788–91

-

Feminine WaveHokusai, mid-19th century

Print production

Ukiyo-e prints were the works of teams of artisans in several workshops;[173] it was rare for designers to cut their own woodblocks.[174] Labour was divided into four groups: the publisher, who commissioned, promoted, and distributed the prints; the artists, who provided the design image; the woodcarvers, who prepared the woodblocks for printing; and the printers, who made impressions of the woodblocks on paper.[175] Normally only the names of the artist and publisher were credited on the finished print.[176]

Ukiyo-e prints were impressed on hand-made paper[177] manually, rather than by mechanical press as in the West.[178] The artist provided an ink drawing on thin paper, which was pasted[179] to a block of cherry wood[i] and rubbed with oil until the upper layers of paper could be pulled away, leaving a translucent layer of paper that the block-cutter could use as a guide. The block-cutter cut away the non-black areas of the image, leaving raised areas that were inked to leave an impression.[173] The original drawing was destroyed in the process.[179]

Prints were made with blocks face up so the printer could vary pressure for different effects, and watch as paper absorbed the water-based sumi ink,[178] applied quickly in even horizontal strokes.[182] Amongst the printer's tricks were embossing of the image, achieved by pressing an uninked woodblock on the paper to achieve effects, such as the textures of clothing patterns or fishing net.[183] Other effects included burnishing[184] rubbing the paper with agate to brighten colours;[185] varnishing; overprinting; dusting with metal or mica; and sprays to imitate falling snow.[184]

The ukiyo-e print was a commercial art form, and the publisher played an important role.[186] Publishing was highly competitive; over a thousand publishers are known from throughout the period. The number peaked at around 250 in the 1840s and 1850s[187]—200 in Edo alone[188]—and slowly shrank following the opening of Japan until about 40 remained at the opening of the 20th century. The publishers owned the woodblocks and copyrights, and from the late 18th century enforced copyrights[187] through the Picture Book and Print Publishers Guild.[j][189][189] Prints that went through several pressings were particularly profitable, as the publisher could reuse the woodblocks without further payment to the artist or woodblock cutter. The woodblocks were also traded or sold to other publishers or pawnshops.[190] Publishers were usually also vendors, and commonly sold each other's wares in their shops.[189] In addition to the artist's seal, publishers marked the prints with their own seals—some a simple logo, others quite elaborate, incorporating an address or other information.[191]

Print designers went through apprenticeship before being granted the right to produce prints of their own that they could sign with their own names.[192] Young designers could be expected to cover part or all of the costs of cutting the woodblocks. As the artists gained fame, publishers usually covered these costs, and artists could demand higher fees.[193]

In pre-modern Japan, people could go by numerous names throughout their lives, their childhood yōmyō personal name different from their zokumyō name as an adult. An artist's name consisted of a gasei—an artist surname—followed by an azana personal art name. The gasei was most frequently taken from the school the artist belonged to, such as Utagawa or Torii,[194] and the azana normally took a Chinese character from the master's art name—for example, many students of Toyokuni (豊国) took the "kuni" (国) from his name, including Kunisada (国貞) and Kuniyoshi (国芳).[192] The names artists signed to their works can be a source of confusion as they sometimes changed names through their careers;[195] Hokusai was an extreme case, using over a hundred names throughout his 70-year career.[196]

The prints were mass-marketed,[186] and by the mid-19th century, the total circulation of a print could run into the thousands.[197] Retailers and travelling sellers promoted them at prices affordable to prosperous townspeople.[198] In some cases, the prints advertised kimono designs by the print artist.[186] From the second half of the 17th century, prints were frequently marketed as part of a series,[191] each print stamped with the series name and the print's number in that series.[199] This proved a successful marketing technique, as collectors bought each new print in the series to keep their collections complete.[191] By the 19th century, series such as Hiroshige's Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō ran to dozens of prints.[199]

- Making ukiyo-e prints

-

Making Prints, Hosoki Toshikazu, 1879

-

The woodblock printing process, Kunisada, 1857. A fantasy version, wholly staffed by well-dressed "beauties". In fact, few women worked in printmaking;[200] Hokusai's daughter Katsushika Ōi was one.

Colour print production

While colour printing in Japan dates to the 1640s, early ukiyo-e prints used only black ink. Colour was sometimes added by hand, using a red lead ink in tan-e prints, or later in a pink safflower ink in beni-e prints. Colour printing arrived in books in the 1720s and in single-sheet prints in the 1740s, with a different block and printing for each colour. Early colours were limited to pink and green; techniques expanded over the following two decades to allow up to five colours.[173] The mid-1760s brought full-colour nishiki-e prints[173] made from ten or more woodblocks.[201] To keep the blocks for each colour aligned correctly, registration marks called kentō were placed on one corner and an adjacent side.[173]

Printers first used natural colour dyes made from mineral or vegetable sources. The dyes had a translucent quality that allowed a variety of colours to be mixed from primary red, blue, and yellow pigments.[202] In the 18th century, Prussian blue became popular, and was particularly prominent in the landscapes of Hokusai and Hiroshige,[202] as was bokashi, where the printer produced gradations of colour or blended one colour into another.[203] Cheaper and more consistent synthetic aniline dyes arrived from the West in 1864. The colours were harsher and brighter than traditional pigments. The Meiji government promoted their use as part of broader policies of Westernization.[204]

Criticism and historiography

Contemporary records of ukiyo-e artists are rare. The most significant is the Ukiyo-e Ruikō ("Various Thoughts on ukiyo-e"), a collection of commentaries and artist biographies. Ōta Nanpo compiled the first, no-longer-extant version around 1790. The work did not see print during the Edo era, but circulated in hand-copied editions that were subject to numerous additions and alterations;[205] over 120 variants of the Ukiyo-e Ruikō are known.[206]

Before World War II, the predominant view of ukiyo-e stressed the centrality of prints; this viewpoint ascribes ukiyo-e's founding to Moronobu. Following the war, thinking turned to the importance of ukiyo-e painting and making direct connections with 17th century Yamato-e paintings; this viewpoint sees Matabei as the genre's originator, and is especially favoured in Japan. This view had become widespread among Japanese researchers by the 1930s, but the militaristic government of the time suppressed it, wanting to emphasize a division between the Yamato-e scroll paintings associated with the court, and the prints associated with the sometimes anti-authoritarian merchant class.[19]

The earliest comprehensive historical and critical works on ukiyo-e came from the West. Ernest Fenollosa was Professor of Philosophy at the Imperial University in Tokyo from 1878, and was Commissioner of Fine Arts to the Japanese government from 1886. His Masters of Ukioye of 1896 was the first comprehensive overview and set the stage for most later works with an approach to the history in terms of epochs: beginning with Matabei in a primitive age, it evolved towards a late-18th century golden age that began to decline with the advent of Utamaro, and had a brief revival with Hokusai and Hiroshige's landscapes in the 1830s.[207] Laurence Binyon, the Keeper of Oriental Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, wrote an account in Painting in the Far East in 1908 that was similar to Fenollosa's, but placed Utamaro and Sharaku amongst the masters. Arthur Davison Ficke built on the works of Fenollosa and Binyon with a more comprehensive Chats on Japanese Prints in 1915.[208] James A. Michener's The Floating World in 1954 broadly followed the chronologies of the earlier works, while dropping classifications into periods and recognizing the earlier artists not as primitives but as accomplished masters emerging from earlier painting traditions.[209] For Michener and his sometime collaborator Richard Lane, ukiyo-e began with Moronobu rather than Matabei.[210] Lane's Masters of the Japanese Print of 1962 maintained the approach of period divisions while placing ukiyo-e firmly within the genealogy of Japanese art. The book acknowledges artists such as Yoshitoshi and Kiyochika as late masters.[211]

Seiichirō Takahashi's Traditional Woodblock Prints of Japan of 1964 placed ukiyo-e artists in three periods: the first was a primitive period that included Harunobu, followed by a golden age of Kiyonaga, Utamaro, and Sharaku, and then a closing period of decline following the declaration beginning in the 1790s of strict sumptuary laws that dictated what could be depicted in artworks. The book nevertheless recognizes a larger number of masters from throughout this last period than earlier works had,[212] and viewed ukiyo-e painting as a revival of Yamato-e painting.[17] Tadashi Kobayashi further refined Takahashi's analysis by identifying the decline as coinciding with the desperate attempts of the shogunate to hold on to power through the passing of draconian laws as its hold on the country continued to break down, culminating in the Meiji Restoration in 1868.[213]

Ukiyo-e scholarship has tended to focus on the cataloguing of artists, an approach that lacks the rigour and originality that has come to be applied to art analysis in other areas. Such catalogues are numerous, but tend overwhelmingly to concentrate on a group of recognized geniuses. Little original research has been added to the early, foundational evaluations of ukiyo-e and its artists, especially with regard to relatively minor artists.[214] While the commercial nature of ukiyo-e has always been acknowledged, evaluation of artists and their works has rested on the aesthetic preferences of connoisseurs and paid little heed to contemporary commercial success.[215]

Standards for inclusion in the ukiyo-e canon rapidly evolved in the early literature. Utamaro was particularly contentious, seen by Fenollosa and others as a degenerate symbol of ukiyo-e's decline; Utamaro has since gained general acceptance as one of the form's greatest masters. Artists of the 19th century such as Yoshitoshi were ignored or marginalized, attracting scholarly attention only towards the end of the 20th century.[216] Works on late-era Utagawa artists such as Kunisada and Kuniyoshi have revived some of the contemporary esteem these artists enjoyed. Many late works examine the social or other conditions behind the art, and are unconcerned with valuations that would place it in a period of decline.[217]

Novelist Jun'ichirō Tanizaki was critical of the superior attitude of Westerners who claimed a higher aestheticism in purporting to have discovered ukiyo-e. He maintained that ukiyo-e was merely the easiest form of Japanese art to understand from the perspective of Westerners' values, and that Japanese of all social strata enjoyed ukiyo-e, but that Confucian morals of the time kept them from freely discussing it, social mores that were violated by the West's flaunting of the discovery.[218]

Since the dawn of the 20th century historians of manga—Japanese comics and cartooning—have developed narratives connecting the art form to pre-20th century Japanese art. Particular emphasis falls on the Hokusai Manga as a precursor, though Hokusai's book is not narrative, nor does the term "manga" originate with Hokusai.[219] In English and other languages, the word "manga" is used in the restrictive sense of "Japanese comics" or "Japanese-style comics",[220] while in Japanese it indicates all forms of comics, cartooning,[221] and caricature.[222]

Collection and preservation

The ruling classes strictly limited the space permitted for the homes of the social classes below them; the relatively small size of ukiyo-e works was ideal for hanging in these homes.[223] Little record of the patrons of ukiyo-e paintings has survived. They sold for considerably higher prices than prints—up to many thousands of times more, and thus must have been purchased by the wealthy, likely merchants and perhaps some from the samurai class.[10] Late-era prints are the most numerous extant examples, as they were produced in the greatest quantities in the 19th century, and the older a print is the less chance it had of surviving.[224] Ukiyo-e was largely associated with Edo, and visitors to Edo often bought what they called azuma-e[l] as souvenirs. Shops that sold them might specialize in products such as hand-held fans, or offer a diverse selection.[189]

The ukiyo-e print market was highly diversified as it sold to a heterogeneous public, from dayworkers to wealthy merchants.[225] Little concrete information is known about production and consumption habits. Detailed records in Edo were kept of a wide variety of courtesans, actors, and sumo wrestlers, but no such records pertaining to ukiyo-e remain—or perhaps ever existed. Determining what is understood about the demographics of ukiyo-e consumption has required indirect means.[226]

Determining at what prices prints sold is a challenge for experts, as records of hard figures are scanty and there was great variety in the production quality, size,[227] supply and demand,[228] and methods, which went through changes such as the introduction of full-colour printing.[229] How expensive prices can be considered is also difficult to determine as social and economic conditions were in flux throughout the period.[230] In the 19th century, records survive of prints selling from as low as 16 mon[231] to 100 mon for deluxe editions.[232] Jun'ichi Ōkubo suggests that prices in the 1920s and 1930s of mon were likely common for standard prints.[233] As a loose comparison, a bowl of soba noodles in the early 19th century typically sold for 16 mon.[234]

The dyes in ukiyo-e prints are susceptible to fading when exposed even to low levels of light; this makes long-term display undesirable. The paper they are printed on deteriorates when it comes in contact with acidic materials, so storage boxes, folders, and mounts must be of neutral pH or alkaline. Prints should be regularly inspected for problems needing treatment, and stored at a relative humidity of 70% or less to prevent fungal discolourations.[235]

The paper and pigments in ukiyo-e paintings are sensitive to light and seasonal changes in humidity. Mounts must be flexible, as the sheets can tear under sharp changes in humidity. In the Edo era, the sheets were mounted on long-fibred paper and preserved scrolled up in plain paulownia wood boxes placed in another lacquer wooden box.[236] In museum settings, display times are heavily limited to prevent deterioration from exposure to light and environmental pollution, and care is taken in the unrolling and rerolling of scrolls, with scrolling causing concavities in the paper, and the unrolling and rerolling of the scrolls causing creasing.[237] The humidity levels that scrolls are kept in are generally between 50 percent and 60 percent, as scrolls kept in too dry an atmosphere become brittle.[238]

Because ukiyo-e prints were mass-produced, collecting them presents considerations different from the collecting of paintings. There is wide variation in the condition, rarity, cost, and quality of extant prints. Prints may have stains, foxing, wormholes, tears, creases, or dogmarks, the colours may have faded, or they may have been retouched. Carvers may have altered the colours or composition of prints that went through multiple editions. When cut after printing, the paper may have been trimmed within the margin.[239] Values of prints depend on a variety of factors, including the artist's reputation, print condition, rarity, and whether it is an original pressing—even high-quality later printings will fetch a fraction of the valuation of an original.[240]