喜多川歌麿(日语:喜多川 歌麿/きたがわ うたまろ Kitagawa Utamaro,1753年—1806年10月31日),是日本浮世绘最著名的大师之一。善画美人画。

生平

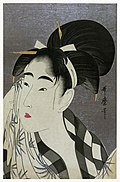

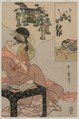

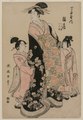

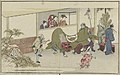

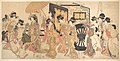

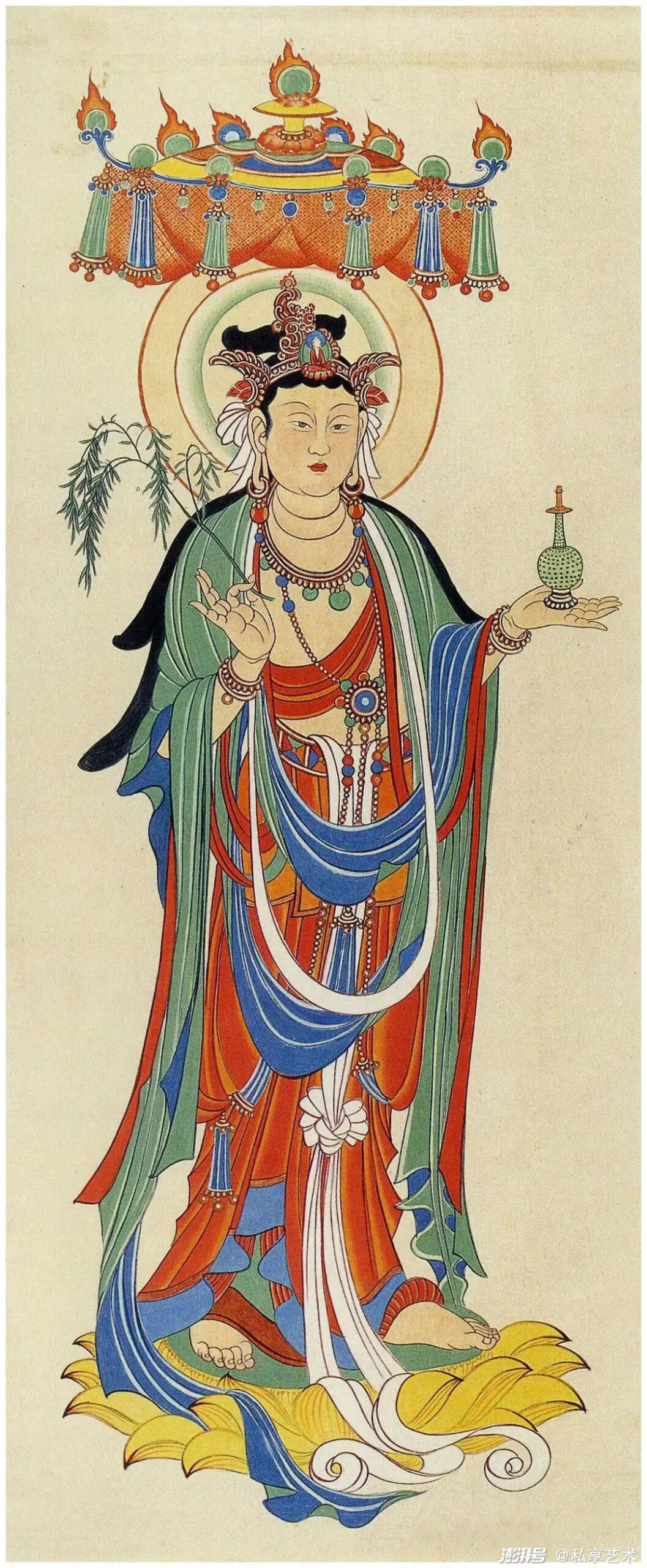

生于江户(今东京)农家,是“大首绘”的创始人,也就是有脸部特写的半身胸像。他对处于社会底层的歌舞伎、大坂贫妓充满同情,并且以纤细高雅的笔触绘制了许多以头部为主的美人画,竭力探究女性内心深处的特有之美。代表作品有《江户宽政年间三美人》——中间是富本丰雏,右为阿北,左为阿久;丰雏是花街吉原艺妓,阿北与阿久是浅草观音堂随身门下茶室的姑娘。

作品

锦絵

- ‘妇女人相十品’ 大判 揃物 约寛政3年‐寛政4年

- ‘妇人相学十躰’ 大判 揃物 约寛政3年‐寛政4年

- ‘歌撰恋之部’ 大判5枚揃 约寛政5年

- ‘娘日时计’ 大判5枚揃 约寛政6年

- ‘北国五色墨’ 大判5枚揃 约寛政7年

- ‘青楼十二时’ 大判12枚揃 寛政中期

- ‘教训亲の目鉴’大判10枚揃 享和1年‐享和2年

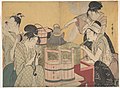

- “针仕事” 大判3枚続 约寛政7年

- “风流七小町”

- “当时全盛美人揃 越前屋内唐土” 大判 东京国立博物馆所蔵

- “当时全盛美人揃 玉屋内しつか” 大判

- “娘日时计 未ノ刻”大判 东京国立博物馆所蔵

- “相合伞”大判 东京国立博物馆所蔵

- “歌枕”

- “针仕事” 大判3枚続の左 城西大学水田美术馆蔵

- “山东京伝游宴” 大判 锦絵3枚続 城西大学水田美术馆蔵

- “音曲比翼の番组” 小むら咲権六 间判 城西大学水田美术馆蔵

- “桥下の钓” 长判 城西大学水田美术馆所蔵

- “北国五色墨 切の娘” 大判 日本浮世绘博物馆蔵

- “高岛おひさ” 大判 大英博物馆蔵

- “高岛おひさ” 细判 檀香山艺术博物馆所蔵 寛政5年顷 両面折(一枚の纸の表面におひさの正面、里面に后ろ姿を折分けている。)

- “歌撰恋之部 稀二逢恋” 大判 大英博物馆藏

- “见立忠臣蔵十一だんめ” 大判2枚続 东京国立博物馆藏 寛政6年‐寛政7年顷 画中に歌麿自身が描かれている。

- “青楼十二时 丑の刻” 大判 寛政6年顷 布鲁塞尔皇家艺术与历史博物馆藏

- “妇人相学十躰 浮気之相” 大判 寛政4年‐寛政5年顷 东京国立博物馆藏

- “妇人相学十躰 ぽっぴんを吹く娘” 大判 寛政4年‐寛政5年顷 檀香山艺术博物馆藏

- “歌撰恋之部 物思恋” 大判 寛政4年‐寛政5年顷 吉美美术馆藏

- “当时三美人” 大判 寛政5年顷 波士顿美术馆藏

- “妇人泊り客之図” 大判3枚続 寛政6年‐寛政7年顷 庆応义塾藏

- “化物の梦” 大判 寛政12年顷 菲茨威廉美术馆藏

絵本

- ‘画本虫撰’ 絵入り狂歌本 天明8年

- ‘歌まくら’ 彩色折艶本 天明8年

- ‘潮干のつと’ 絵入り狂歌本 寛政1年‐寛政2年顷

肉笔浮世絵

| 作品名 | 技法 | 形状・员数 | 落款・印章 | 制作年 | 所有者 | 备考 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 雨中汤帰り図 | 绢本着色 | 额1面(元1幅) | 落款“哥丸舎豊章画” 印章“鱼水有清言” | 天明中期 | 个人蔵(アメリカ) | |

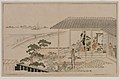

| 品川の月図 | 纸本着色 | 1幅 | 无款 | 天明末期 | フリーア美术馆 | 吉原の花、深川の雪との连作。 |

| 游女と秃図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿画” 印章“岸识之印?”朱文方印“字子华白?”朱文方印 | 寛政初期 | ボストン美术馆 | |

| かくれんぼ図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿画” 印章“岸识之印?”朱文方印“字子华白?”朱文方印 | 寛政初期 | 镰仓国宝馆 | 特殊な落款・印章が一致することから、上记の游女と秃図と双幅か、3幅対のうちの2点だと推测される。 |

| 游女と秃図 | 纸本墨画 | 1幅 | 落款“喜多川歌麿源豊章画” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 寛政2-5年 | 个人蔵 | 山东京伝赞[1] |

| 游女と秃図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“歌麿画” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 寛政3-5年 | 城西大学水田美术馆 | |

| 女达磨図 | 纸本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“歌麿画” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 寛政3-5年 | 栃木市 | 中国から输入された竹纸が使われている。 |

| 三福神の相扑図 | 纸本墨画淡彩 | 1幅 | 落款“歌麿画” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 寛政3-5年 | 栃木市 | |

| 锺馗図 | 纸本墨画 | 1幅 | 落款“喜多川歌麿源豊章画” 方印未読 | 寛政3-5年 | 栃木市 | |

| 万才図额 | 绢本着色 | 4面(二曲一只) | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 寛政3-5年 | 镰仓国宝馆 | 元は引き手袄。 |

| 福禄寿三星図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“歌麿源豊章図” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 寛政3-5年 | 日本浮世絵博物馆 | |

| 吉原の花図 | 纸本着色 | 1幅 | 无款 | 寛政3-4年 | ワズワース・アセーニアム(米国) | 品川の月、深川の雪との连作。 |

| 纳凉美人図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“歌麿画” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 寛政5-8年 | 个人蔵 | |

| 花魁道中図 | 纸本墨画淡彩 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 寛政5-8年 | ミシガン大学付属美术馆(米国)所蔵 | 山东京伝赞 |

| 游女と秃図 | 绢本墨画淡彩 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 寛政5-8年 | 千叶市美术馆 | |

| 夏姿美人図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 寛政5-8年 | 远山记念馆 | |

| 立姿美人図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“歌麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 寛政5-8年 | 个人蔵(国内) | 重要美术品 |

| 纳凉美人図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 寛政5-8年 | 千叶市美术馆 | 重要美术品 |

| 美人読玉章図(びじん たまずさをよむず) | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 寛政5-8年 | 浮世絵太田记念美术馆 | |

| 寒泉浴〈入浴〉図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 寛政中后期 | MOA美术馆 | 大田南亩赞 |

| 桟桥二美人図 | 绢纸本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 寛政中后期 | MOA美术馆 | |

| 三美人図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 寛政后期 | 冈田美术馆 | |

| 游女と二人の秃図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 寛政后期 | キヨッソーネ东洋美术馆 | |

| 三美人図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 寛政后期 | 海の见える杜美术馆 | 麻生工芸美术馆旧蔵。歌麿の寛政后期の基准作 |

| 美人と若众図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“きた川歌麿”朱・白文方印 | 1802年(享和2年)顷か | ニューオータニ美术馆 | 重要美术品(1938年(昭和13年)指定)。印章は中央に白文で“歌麿”とあり、その左右に朱文のくずし字で“きた・川”という他に类例がない珍しい印である[2]。 |

| 二美人図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 享和期顷 | メトロポリタン美术馆 | |

| 朝妆美人図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 享和期顷 | 大英博物馆 | |

| 男と娘(つぼみ)図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“歌”“麿”朱文方形连印 | 享和期顷 | 个人蔵 | 春画。 |

| 娘と子ども図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“歌麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 享和期顷 | 出光美术馆 | |

| 芸妓図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿笔” | 享和期顷 | 冈田美术馆 | |

| 男女游爱図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 享和-文化初期 | 个人蔵 | 春画。歌麿の肉笔春画は、上记の“男と娘図”と本作の2点しか确认されていない。 |

| 更衣美人図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“歌麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 文化年间初期(1804年 - 1805年) | 出光美术馆 | 重要文化财 |

| 三味线を弾く美人図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 享和-文化初期 | ボストン美术馆 | |

| 花魁道中図 | 纸本墨画淡彩 | 扇1面 | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“歌”“麿”朱文方形连印 | 享和-文化初期 | 东京国立博物馆 | |

| 月见の母と娘図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 享和-文化初期 | 香雪美术馆 | |

| 芥川図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“哥麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 享和-文化初期 | ロシア国立东洋美术馆 | |

| 三味线を弾く游女図 | 绢本着色 | 1幅 | 落款“歌麿笔” 印章“歌麿”朱文方印 | 享和-文化初期 | フリーア美术馆 | |

| 深川の雪図 | 纸本着色 | 1幅 | 无款 | 享和-文化初期 | 冈田美术馆 | 深川の月、吉原の花との连作。 |

其他

JR东日本于2007年3月28日发行的外国人专用Suica + N'EX Yokoso! Japan套票第一弹,卡面图案即为歌麿所绘的《江户宽政年间三美人》图,仅于成田国际机场贩售。

参考

Kitagawa Utamaro (喜多川 歌麿; Japanese pronunciation: [ɯ.ta.ma.ɾo],[1] c. 1753 – 31 October 1806) was a Japanese artist. He is one of the most highly regarded designers of ukiyo-e woodblock prints and paintings, and is best known for his bijin ōkubi-e "large-headed pictures of beautiful women" of the 1790s. He also produced nature studies, particularly illustrated books of insects.

Little is known of Utamaro's life. His work began to appear in the 1770s, and he rose to prominence in the early 1790s with his portraits of beauties with exaggerated, elongated features. He produced over 2000 known prints and was one of the few ukiyo-e artists to achieve fame throughout Japan in his lifetime. In 1804 he was arrested and manacled for fifty days for making illegal prints depicting the 16th-century military ruler Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and died two years later.

Utamaro's work reached Europe in the mid-nineteenth century, where it was very popular, enjoying particular acclaim in France. He influenced the European Impressionists, particularly with his use of partial views and his emphasis on light and shade, which they imitated. The reference to the "Japanese influence" among these artists often refers to the work of Utamaro.

Background

Ukiyo-e art flourished in Japan during the Edo period from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. The art form took as its primary subjects courtesans, kabuki actors, and others associated with the ukiyo "floating world" lifestyle of the pleasure districts. Alongside paintings, mass-produced woodblock prints were a major form of the genre.[2] Ukiyo-e art was aimed at the common townspeople at the bottom of the social scale, especially of the administrative capital of Edo. Its audience, themes, aesthetics, and mass-produced nature kept it from consideration as serious art.[3]

In the mid-eighteenth century, full-colour nishiki-e prints became common. They were printed by using a large number of woodblocks, one for each colour.[4] Towards the close of the eighteenth century there was a peak in both quality and quantity of the work.[5] Kiyonaga was the pre-eminent portraitist of beauties during the 1780s, and the tall, graceful beauties in his work had a great influence on Utamaro, who was to succeed him in fame.[6] Shunshō of the Katsukawa school introduced the ōkubi-e "large-headed picture" in the 1760s.[7] He and other members of the Katsukawa school, such as Shunkō, popularized the form for yakusha-e actor prints, and popularized the dusting of mica in the backgrounds to produce a glittering effect.[8]

Biography

Early life

Little is known of Utamaro's life. He was born Kitagawa Ichitarō[a] in c. 1753.[10] As an adult, he was known by the given names Yūsuke,[b] and later Yūki.[c][11] Early accounts have given his birthplace as Kyoto, Osaka, Yoshiwara in Edo (modern Tokyo), or Kawagoe in Musashi Province (modern Saitama Prefecture); none of these places has been verified. The names of his parents are not known; it has been suggested his father may have been a Yoshiwara teahouse owner, or Toriyama Sekien,[10] an artist who tutored him[12] and who wrote of Utamaro playing in his garden as a child.[10]

Apparently, Utamaro married, although little is known about his wife and there is no record of their having had children. There are, however, many prints of tender and intimate domestic scenes featuring the same woman and child over several years of the child's growth among his works.

Apprenticeship and early work

Sometime during his childhood Utamaro came under the tutelage of Sekien, who described his pupil as bright and devoted to art.[12] Sekien, although trained in the upper-class Kanō school of Japanese painting, had become in middle age a practitioner of ukiyo-e and his art was aimed at the townspeople in Edo. His students included haiku poets and ukiyo-e artists such as Eishōsai Chōki.[13]

Utamaro's first published work may be an illustration of eggplants in the haikai poetry anthology Chiyo no Haru[d] published in 1770. His next known works appear in 1775 under the name Kitagawa Toyoaki,[e][15]—the cover to a kabuki playbook entitled Forty-eight Famous Love Scenes[f] which was distributed at the Edo playhouse Nakamura-za.[14] As Toyoaki, Utamaro continued as an illustrator of popular literature for the rest of the decade, and occasionally produced single-sheet yakusha-e portraits of kabuki actors.[16]

The young, ambitious publisher Tsutaya Jūzaburō enlisted Utamaro and in the autumn of 1782 the artist hosted a lavish banquet whose list of guests included artists such as Kiyonaga, Kitao Shigemasa, and Katsukawa Shunshō, as well as writers such as Ōta Nanpo (1749–1823)and Hōseidō Kisanji. It was at this banquet that it is believed the artist first announced his new art name, Utamaro. Per custom, he distributed a specially made print for the occasion, in which, before a screen bearing the names of his guests, is a self-portrait of Utamaro making a deep bow.[17]

Utamaro's first work for Tsutaya appeared in a publication dated as 1783: The Fantastic Travels of a Playboy in the Land of Giants,[g] a kibyōshi picture book created in collaboration with his friend Shimizu Enjū, a writer.[h] In the book, Tsutaya described the pair as making their debuts.[i][19]

At some point in the mid-1780s, probably 1783, he went to live with Tsutaya Jūzaburō. It is estimated that he lived there for approximately five years. He seems to have become a principal artist for the Tsutaya firm. Evidence of his prints for the next few years is sporadic, as he mostly produced illustrations for books of kyōka ("crazy verse"), a parody of the classical waka form. None of his work produced during the period 1790–1792 has survived.

Height of fame

In about 1791 Utamaro gave up designing prints for books and concentrated on making single portraits of women displayed in half-length, rather than the prints of women in groups favoured by other ukiyo-e artists.

In 1793 he achieved recognition as an artist, and his semi-exclusive arrangement with the publisher Tsutaya Jūzaburō ended. Utamaro then went on to produce several series of well-known works, all featuring women of the Yoshiwara district.

Over the years, he also created a number of volumes of animal, insect, and nature studies and shunga, or erotica. Shunga prints were quite acceptable in Japanese culture, not associated with a negative concept of pornography as found in western cultures, but considered rather as a natural aspect of human behavior and circulated among all levels of Japanese society.[20]

Later life

Tsutaya Jūzaburō died in 1797, and Utamaro thereafter lived in Kyūemon-chō, then Bakuro-chō, and finally near the Benkei Bridge.[21] Utamaro was apparently very upset by the loss of his long-time friend and supporter. Some commentators feel that after this event, his work never reached the heights previously attained.[who?]

A law went into effect in 1790 requiring prints to bear a censor's seal of approval to be sold. Censorship increased in strictness over the following decades, and violators could receive harsh punishments. From 1799 even preliminary drafts required approval.[22] A group of Utagawa-school offenders including Toyokuni had their works repressed in 1801.[23] In 1804, Utamaro ran into legal trouble over a series of prints of samurai warriors, with their names slightly disguised; the depiction of warriors, their names, and their crests was forbidden at the time. Records have not survived of what sort of punishment Utamaro received.[24]

Arrest of 1804

The Ehon Taikōki,[j] published from 1797 to 1802, detailed the life of the 16th-century military ruler, Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The work was widely adapted, such as for kabuki and bunraku theatre. When artists and writers put out prints and books based on the Ehon Taikōki in the disparaged ukiyo-e style, it attracted reprisals from the government. In probably the most famous case of censorship of the Edo period,[25] Utamaro was imprisoned in 1804,[k] after which he was manacled along with Tsukimaro, Toyokuni, Shuntei, Shun'ei, and Jippensha Ikku for fifty days and their publishers subjected to heavy fines.[27]

Government documents of the case are no longer extant, and there are few other documents relating to the incident. It appears that Utamaro was most prominent of the group. The artists might have offended the authorities by identifying the historical figures by name and with their identifying crests and other symbols, which was prohibited, and by depicting Hideyoshi with prostitutes[l] of the pleasure quarters.[28] Utamaro's censored prints include one of the daimyō Katō Kiyomasa lustily gazing at a Korean dancer at a party,[29] another of Hideyoshi holding the hand of his page Ishida Mitsunari in a sexually suggestive manner,[30] and another of Hideyoshi with his five consorts viewing the cherry blossoms at the temple Daigo-ji in Kyoto, a historical event famous for displaying Hideyoshi's extravagance. This last displays the names of each consort while placing them in the typical poses of courtesans at a Yoshiwara party.[31]

- Utamaro prints censored in 1804

-

Katō Kiyomasa at a party with Korean dancers

-

Hideyoshi and his Five Wives Viewing the Cherry-blossoms at Higashiyama

Death

Records give Utamaro's death date as the 20th day of the 9th month of the year Bunka, which equates to 31 October 1806.[10] He was given the Buddhist posthumous name Shōen Ryōkō Shinshi.[m][32] Apparently with no heirs, his tomb at the temple Senkōji was left untended. A century later, in 1917, admirers of Utamaro had the decayed grave repaired.[32]

Pupils

Utamaro had a number of pupils, who took names such as Kikumaro (later Tsukimaro), Hidemaro, and Takemaro. These artists produced works in the master's style, though none are considered of Utamaro's quality. Sometimes he allowed them to sign his name. Of his students, Koikawa Shunchō married Utamaro's widow on the master's death and took on the name Utamaro II.[33] After 1820 he produced his work under the name Kitagawa Tetsugorō.[34]

Analysis

[Utamaro] created an absolutely new type of female beauty. At first he was content to draw the head in normal proportions and quite definitely round in shape; only the neck on which this head was posed was already notably slender ... Towards the middle of the tenth decade these exaggerated proportions of the body had reached such an extreme that the heads were twice as long as they were broad, set upon slim long necks, which in turn swayed upon very slim shoulders; the upper coiffure bulged out to such a degree that it almost surpassed the head itself in extent; the eyes were indicated by short slits, and were separated by an inordinately long nose from an infinitesimally small mouth; the soft robes hung loosely about figures of an almost unearthly thinness.

— Woldemar von Seidlitz, Geschichte des japanischen Farbenholzschnittes, 1897[35]

What little information about Utamaro's life that has been passed down is often contradictory, so analysis of his development as an artist relies chiefly on his work itself.[10] Utamaro is known primarily for his bijin-ga portraits of female beauties, though his work ranges from kachō-e "flower-and-bird pictures" to landscapes to book illustrations.[34]

Utamaro's early bijin-ga follow closely the example of Kiyonaga. In the 1790s his figures became more exaggerated, with thin bodies and long faces with small features.[35] Utamaro experimented with line, colour, and printing techniques to bring out subtle differences in the features, expressions, and backdrops of subjects from a wide variety of class and background. Utamaro's individuated beauties were in sharp contrast to the stereotyped, idealized images that had been the norm.[36]

By the end of the 1790s, especially following the death of his patron Tsutaya Jūzaburō in 1797, Utamaro's prodigious output declined in quality.[37] By 1800 his exaggerations had become more extreme, with faces three times as long as they are wide and body proportions of eight heads length to the body. By this point, critics such as Basil Stewart consider Utamaro's figures to "lose much of their grace";[35] these later works are less prized amongst collectors.[citation needed]

Utamaro produced more than two thousand prints during his working career, amongst which are over 120 bijin-ga print series. He made illustrations for nearly 100 books and about 30 paintings.[15] He also created a number of paintings and surimono, as well as many illustrated books, including more than thirty shunga books, albums, and related publications. Among his best-known works are the series Ten Studies in Female Physiognomy, A Collection of Reigning Beauties, Great Love Themes of Classical Poetry (sometimes called Women in Love containing individual prints such as Revealed Love and Pensive Love), and Twelve Hours in the Pleasure Quarters.[citation needed] His work appeared from at least 60 publishers, of which Tsutaya Jūzaburō and Izumiya Ichibei were the most important.[15]

He alone, of his contemporary ukiyo-e artists, achieved a national reputation during his lifetime. His sensuous beauties generally are considered the finest and most evocative bijinga in all of ukiyo-e.[38]

He succeeded in capturing the subtle aspects of personality and the transient moods of women of all classes, ages, and circumstances. His reputation has remained undiminished since. Kitagawa Utamaro's work is known worldwide, and he generally is regarded as one of the half-dozen greatest ukiyo-e artists of all time.[39]

Legacy

Utamaro was recognized as a master in his own age. He appears to have achieved a national reputation at a time when even the most popular Edo ukiyo-e artists were little known outside the city.[40] Due to his popularity Utamaro had many imitators, some of whom likely signed their work with his name; this is believed to include students of his and his successor, Utamaro II.[33] On rare occasions Utamaro signed his work "the genuine Utamaro"[n] to distinguish himself from these imitators.[34] Forgeries and reprints of Utamaro's work are common; he produced a large body of work, but his earlier, more popular works are difficult to find in good condition.[41]

The Coiffure, drypoint and aquatint, c. 1890–91

A wave of interest in Japanese art swept France from the mid-19th century, called Japonisme. Exhibitions in Paris of Japanese art began to be staged in the 1880s, include an Utamaro exhibition in 1888 by the German-French art dealer Siegfried Bing.[42] The French Impressionists regarded Utamaro's work on a level akin with Hokusai and Hiroshige.[43] French artist-collectors of Utamaro's work included Monet,[44] Degas,[45] Gauguin,[46] and Toulouse-Lautrec[47]

Utamaro had an influence on the compositional, colour,[48] and sense of tranquility of the American painter Mary Cassatt's work.[49] The shin-hanga ("new prints") artist Goyō Hashiguchi (1880–1921) was called the "Utamaro of the Taishō period" (1912–1926) for his manner of depicting women.[50] The painter character Seiji Moriyama in the British novelist Kazuo Ishiguro's An Artist of the Floating World (1986) has a reputation as a "modern Utamaro" for his combination of Western techniques Utamaro-like feminine subjects.[51]

In 2016 Utamaro's Fukaku Shinobu Koi set the record price for an ukiyo-e print sold at auction at €745000.[52]

The 2016 role-playing game Persona 5 has a character named Yusuke Kitagawa after Utamaro's surname.

Historiography

The only surviving official record of Utamaro is a stele at Senkō-ji Temple, which gives his death date as the 20th day of the 9th month of the year Bunka, which equates to 31 October 1806. The record states he was 54 by East Asian age reckoning, by which age begins at 1 rather than 0. From this a birth year of c. 1753 is deduced.[10][10]

Utamaro has gained general acceptance as one of the form's greatest masters.[53] The earliest document of ukiyo-e artists, Ukiyo-e Ruikō, was first compiled while Utamaro was active. The work was not printed, but exists in various manuscripts that different writers altered and expanded. The earliest surviving copy, the Ukiyo-e Kōshō, wrote of Utamaro:[54]

- Kitagawa Utamaro, personal name Yūsuke

- At the start entered the studio of Toriyama Sekien and studied pictures in the Kanō school. Later drew pictures of the styles and manners of men and women and resided temporarily with ezōshiya Tsutaya Jūzaburō. Now lives in Benkeibashi. Many nishiki-e.[54]

The earliest comprehensive historical and critical works on ukiyo-e came from the West,[55] and often denied Utamaro a place in the ukiyo-e canon.[53] Ernest Fenollosa's Masters of Ukioye of 1896 was the first such overview of ukiyo-e. The book posited ukiyo-e as having evolved towards a late-18th-century golden age that began to decline with the advent of Utamaro,[55] which he condemned for his "gradual elongation of the figure, and an adoption of violent emotion and extravagant attitudes". Fenollosa had harsher criticism for Utamaro's pupils, who he considered to have "carried the extravagances of their teacher to a point of ugliness".[56] In his Chats on Japanese Prints of 1915, Arthur Davison Ficke concurred that with Utamaro ukiyo-e entered a period of exaggerated, manneristic decadence.[57]

Laurence Binyon, the Keeper of Oriental Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, wrote an account in Painting in the Far East in 1908 that was similar to Fenollosa's, considering the 1790s a period of decline, but placing Utamaro amongst the masters.[58] He called Utamaro "one of the world's artists for the intrinsic qualities of his genius" and "the greatest of all the figure-designers" in ukiyo-e, with a "far greater resource of composition" than his peers and an "endless" capacity for "unexpected invention".[59] James A. Michener re-evaluated the development of ukiyo-e in The Floating World of 1954, in which he places the 1790s as "the culminating years of ukiyo-e", when "Utamaro brought the grace of Sukenobu to its apex".[59] Seiichirō Takahashi's Traditional Woodblock Prints of Japan of 1964 set the golden age of ukiyo-e at the period of Kiyonaga, Utamaro, and Sharaku, followed by a period of decline with the declaration beginning in the 1790s of strict sumptuary laws that dictated what could be depicted in artworks.[60]

The French art critic Edmond de Goncourt published Outamaro, the first monograph on Utamaro, in 1891,[61] with help from the Japanese art dealer Tadamasa Hayashi.[62] British ukiyo-e scholar Jack Hillier had the monograph Utamaro: Colour Prints and Paintings published in 1961.[63]

Print series

A partial list of his print series and their dates includes:

- Utamakura (1788) attributed

- Chosen Poems (1791–1792)

- Ten Types of Women's Physiognomies (1792–1793)

- Famous Beauties of Edo (1792–1793)

- Ten Learned Studies of Women (1792–1793)

- Anthology of Poems: The Love Section (1793–1794)

- Snow, Moon, and Flowers of the Green Houses (1793–1795)

- Five Shades of Ink in the Northern Quarter (1794–1795)

- Array of Supreme Beauties of the Present Day (1794)

- Twelve Hours of the Green Houses (1794–1795)

- Renowned Beauties from the Six Best Houses (1795–96)

- Flourishing Beauties of the Present Day (1795–1797)

- An Array of Passionate Lovers (1797–1798)

- Ten Forms of Feminine Physiognomy (1802)

Paintings

Gallery

-

Women playing with the mirror, 1797

-

Hairdresser from the series Twelve types of women's handicraft

-

Woman drinking wine

-

Hari-shigoto ("Needlework"), c. 1794–95

-

The Courtesan Ichikawa of the Matsuba Establishment from the series Famous Beauties of Edo

-

Karagoto of the House of Chojiya in Edo-cho Nichome from the series A Comparison of Courtesan Flowers

-

Tsuitate no Danjo, c. 1797

-

Mother and Child

-

Man lubricating a male prostitute while someone in the background peeks through the curtains and watches

-

Young lady blowing on a poppin

Notes

- ^ Kitagawa Ichitarō (北川市太郎); note the spelling 北川 differs from the spelling 喜多川 Utamaro used as an artist.[9]

- ^ Yūsuke (勇助)[9]

- ^ Yūki (勇記)[9]

- ^ 千代の春 Chiyo no haru, "Eternal Spring"

- ^ Kitagawa Toyoaki (北川豊章); "北川豊章" may also read "Toyoakira".[14]

- ^ Forty-eight Famous Loves Scenes, (四十八手 恋所訳, Shijū Hatte Koi no Showake)

- ^ Migi no Tōri Tashika ni Uso Shikkari Gantori-chō (右通慥而啌多雁取帳)[17]

- ^ Shimizu Enjū (志水燕十)

- ^ Utamaro and Enjū appeared to have worked on a previous book together during 1781: A Short History of the Sartorial Exploits of a Great Connoisseur of Inari Machi (身貌大通神略縁起, Minari Daitsūjin Ryakuengi), which Utamaro signed as "Utamaro, Dilettante of Shinobugaoka". Kiyoshi Shibui suggests the publication of the work may have been delayed.[18]

- ^ 絵本太閤記 Ehon Taikōki, "Illustrated Chronicles of the Regent"; seven parts in eighty-four volumes; text by Takeuchi Kakusai, based on an early Taikōki by Ose Hoan; illustrations by Okada Gyokuzan[25]

- ^ 23 June 1804, according to Ōta Nanpo's diary[26]

- ^ 遊女 yūjo

- ^ Shōen Ryōkō Shinshi (秋円了教信士)[9]

- ^ 正銘歌麿 Shōmei Utamaro

References

- ^ Kindaichi, Haruhiko; Akinaga, Kazue, eds. (10 March 2025). 新明解日本語アクセント辞典 (in Japanese) (2nd ed.). Sanseidō.

- ^ Fitzhugh 1979, p. 27.

- ^ Kobayashi 1982, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 80–83.

- ^ Kobayashi 1997, p. 91.

- ^ Lane 1962, p. 220.

- ^ Kondō 1956, p. 14.

- ^ Gotō 1975, p. 81.

- ^ a b c d Gotō 1975, p. 74.

- ^ a b c d e f g Collia-Suzuki 2008, p. 10.

- ^ Gotō 1975, p. 74; Kobayashi 1982, p. 72.

- ^ a b Kobayashi 1982, p. 72.

- ^ Kobayashi 1982, pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b Kobayashi 1982, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Marks 2012, p. 76.

- ^ Kobayashi 1982, p. 75.

- ^ a b Kobayashi 1982, p. 76.

- ^ Kobayashi 1982, p. 79.

- ^ Kobayashi 1982, pp. 76, 79.

- ^ Hayakawa, Monta; Gerstle, C. Andrew (2013). "Who Were the Audiences for "Shunga?"". Japan Review. 26: 17–36.

- ^ Goncourt, Locey & Locey 2012, p. 11.

- ^ Michener 1954, p. 231.

- ^ Lane 1962, p. 224.

- ^ Collia-Suzuki 2008, p. 30.

- ^ a b Davis 2007, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Davis 2007, p. 290.

- ^ Davis 2007, p. 292.

- ^ Davis 2007, pp. 289–291.

- ^ Davis 2007, p. 304.

- ^ Davis 2007, p. 305.

- ^ Davis 2007, pp. 306–308.

- ^ a b Kobayashi 1982, p. 93.

- ^ a b Goncourt, Locey & Locey 2012, p. 21.

- ^ a b c Stewart 1922, p. 45.

- ^ a b c Stewart 1922, p. 44.

- ^ Kobayashi 1997, p. 88.

- ^ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Harris, Frederick (2010). Ukiyo-e: The Art of the Japanese Print. Tuttle Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 978-4805310984.

- ^ "Ukiyo-e Artists - artelino". www.artelino.com. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ Kobayashi 1982, p. 69.

- ^ Stewart 1922, p. 46.

- ^ Hokenson 2004, p. 186.

- ^ Ives 1974, p. 13.

- ^ Fraleigh & Nakamura 2006, p. 96.

- ^ Dumas 1997, p. 16.

- ^ Ives 1974, p. 96.

- ^ Ives 1974, p. 79.

- ^ Clement, Houzé & Erbolato-Ramsey 2000, p. 60.

- ^ Weinberg 2009, p. 238.

- ^ Brown 2006, p. 22; Seton 2010, p. 81.

- ^ Lewis 2000, p. 56.

- ^ AFP–Jiji staff 2016.

- ^ a b Bell 2004, pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b Davis 2004, p. 120.

- ^ a b Bell 2004, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Bell 2004, p. 7.

- ^ Bell 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Bell 2004, pp. 8–10.

- ^ a b Bell 2004, p. 10.

- ^ Bell 2004, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Bell 2004, p. 18.

- ^ Pasler 1986, p. 275.

- ^ Bell 2004, p. 308.

Works cited

- AFP–Jiji staff (23 June 2016). "Utamaro woodblock print fetches world-record €745,000 in Paris". AFP–Jiji Press. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- Bell, David (2004). Ukiyo-e Explained. Global Oriental. ISBN 978-1-901903-41-6.

- Brown, Kendall H. (2006). "Impressions of Japan: Print Interactions East and West". In Javid, Christine (ed.). Color Woodcut International: Japan, Britain, and America in the Early Twentieth Century. Chazen Museum of Art. pp. 13–29. ISBN 978-0-932900-64-7.

- Clement, Russell T.; Houzé, Annick; Erbolato-Ramsey, Christiane (2000). The Women Impressionists: A Sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-30848-2.

- Collia-Suzuki, Gina (2008). Utamaro Revealed: A Guide to Subjects, Themes & Motifs. Nezu Press. ISBN 978-0955979606.

- Davis, Julie Nelson (2004). "Artistic Identity and Ukiyo-e Prints: The Representation of Kitagawa Utamaro to the Edo Public". In Takeuchi, Melinda (ed.). The Artist as Professional in Japan. Stanford University Press. pp. 113–151. ISBN 978-0-8047-4355-6.

- Davis, Julie Nelson (2007). "The Trouble with Hideyoshi: Censoring Ukiyo-e and the Ehon Taikōki Incident of 1804". Japan Forum. 19 (3). British Association for Japanese Studies: 281–315. doi:10.1080/09555800701579933. ISSN 1469-932X. S2CID 143374782.

- Dumas, Ann (1997). The Private Collection of Edgar Degas. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-797-6.

- Fitzhugh, Elisabeth West (1979). "A Pigment Census of Ukiyo-E Paintings in the Freer Gallery of Art". Ars Orientalis. 11. Freer Gallery of Art, The Smithsonian Institution and Department of the History of Art, University of Michigan: 27–38. JSTOR 4629295.

- Fraleigh, Sondra; Nakamura, Tamah (2006). Hijikata Tatsumi and Ohno Kazuo. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-25785-0.

- Goncourt, Edmond de; Locey, Michael; Locey, Lenita (2012). Utamaro. Parkstone International. ISBN 978-1-78042-928-1.

- Gotō, Shigeki, ed. (1975). Ukiyo-e Taikei 浮世絵大系 [Ukiyo-e Compendium] (in Japanese). Vol. 5. Shueisha. OCLC 703810551.

- Hokenson, Jan (2004). Japan, France, and East-West Aesthetics: French Literature, 1867–2000. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4010-4.

- Ives, Colta Feller (1974). The Great Wave: The Influence of Japanese Woodcuts on French Prints. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-228-5.

- Kobayashi, Tadashi (1982). Utamaro: Portraits from the Floating World. Translated Mark A. Harbison (Revised ed.). Kodansha. ISBN 4-7700-2730-3.

- Kobayashi, Tadashi (1997). Ukiyo-e: An Introduction to Japanese Woodblock Prints. Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4-7700-2182-3.

- Kondō, Ichitarō (1956). Kitagawa Utamaro (1753–1806). Translated by Charles S. Terry. Tuttle. OCLC 613198.[ISBN missing]

- Lane, Richard (1962). Masters of the Japanese Print: Their World and Their Work. Doubleday. OCLC 185540172.[ISBN missing]

- Lewis, Barry (2000). Kazuo Ishiguro. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-5514-0.

- Marks, Andreas (2012). Japanese Woodblock Prints: Artists, Publishers and Masterworks: 1680–1900. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4629-0599-7.

- Michener, James Albert (1954). The Floating World. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0873-0.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Pasler, Jann (1986). Confronting Stravinsky: Man, Musician, and Modernist. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05403-5.

- Seton, Alistair (2010). Collecting Japanese Antiques. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-4-8053-1122-6.

- Stewart, Basil (1922). A Guide to Japanese Prints and Their Subject Matter. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-23809-8.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Weinberg, Helene Barbara (2009). American Impressionism & Realism: A Landmark Exhibition from the MET, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-876509-99-6.

Further reading

- Siegfried Bing, The Art of Utamaro, (The Studio, February 1895)

- Jack Hillier, Utamaro: Color Prints and Paintings (Phaidon, London, 1961)

- Muneshige Narazaki, Sadao Kikuchi, (translated John Bester), Masterworks of Ukiyo-E: Utamaro (Kodansha, Tokyo, 1968)

- Shugo Asano, Timothy Clark, The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro (British Museum Press, London, 1995)

- Julie Nelson Davis, Utamaro and the Spectacle of Beauty (Reaktion Books, London, and University of Hawai'i Press, 2007)

- Gina Collia-Suzuki, The Complete Woodblock Prints of Kitagawa Utamaro: A Descriptive Catalogue (Nezu Press, 2009) - complete catalogue raisonné

External links

- Works by Utamaro in the British Museum

- Exploring the World of Kitagawa Utamaro

- Utamaro's books in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

- Kitagawa Utamaro Online at www.artcyclopedia.com

- Songs of the garden, the "Insect Book" by Utamaro, from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries (fully available online as PDF)

Kitagawa Utamaro(喜多川歌麿, 1753 – September 20, 1806) was a Japanese printmaker and painter, and is considered one of the greatest artists of woodblock prints (ukiyo-e).

子分类

本分类有以下4个子分类,共有4个子分类。

分类“Kitagawa Utamaro”中的媒体文件

以下200个文件属于本分类,共355个文件。

(上一页)(下一页)-

A parody with four beauties (Kitagawa Utamaro).jpg 640 × 470;127 KB

-

Afbeeldingen van Fugen Fugenzô (titel op object), RP-P-1970-65.jpg 4,352 × 6,662;10.01 MB

-

Aikyo zumo LCCN2008660848.jpg 5,526 × 8,322;8.14 MB

-

Ase o fuku onna LCCN2008660689.jpg 6,079 × 9,236;8.13 MB

-

Ase o fuku onna.jpg 6,079 × 9,236;37.56 MB

-

Ase o fuku onna2.jpg 6,079 × 9,236;44.7 MB

-

Avondscene in een theehuis, RP-P-1960-13-4.jpg 6,362 × 4,282;3.08 MB

-

Beauty with a waitress holding a tray (5759527422).jpg 400 × 2,002;322 KB

-

Brooklyn Museum - Along the Shore of Yènoshim - Kitagawa Utamaro.jpg 500 × 768;118 KB

-

Brooklyn Museum - Large Head and Bust Portrait of Beauty - Kitagawa Utamaro.jpg 1,027 × 1,536;389 KB

-

Brooklyn Museum - Pearl Divers - Kitagawa Utamaro.jpg 1,069 × 1,536;586 KB

-

Brooklyn Museum - Still Life Flowers - Kitagawa Utamaro.jpg 590 × 768;93 KB

-

Brooklyn Museum - Travels Looking at Mt. Fuji - Kitagawa Utamaro.jpg 768 × 518;106 KB

-

Busteportret van jonge vrouw met waaier, RP-P-1962-130.jpg 4,116 × 5,998;3.35 MB

-

Suited to Patterns Stocked by Izugura - Kitagawa Utamaro I - 1804-1806.jpg 2,422 × 3,806;3.53 MB

-

Cherry Blossom Viewing at Mimeguri by Kitagawa Utamaro, 1799.JPG 3,036 × 1,544;689 KB

-

Chrysanten in vaas, AK-MAK-1160.jpg 4,059 × 6,009;4.75 MB

-

Chrysanten in vaas-Rijksmuseum AK-MAK-1160.jpeg 1,813 × 2,713;2.26 MB

-

Chōfu no tamagawa LCCN2009615325.jpg 803 × 1,024;180 KB

-

Cleaning of a Samurai house for New Year's festivities (5759527638).jpg 1,657 × 1,215;779 KB

-

Cleaning of a Yoshiwara house for New Year's festivities (5759527582).jpg 1,573 × 1,173;684 KB

-

Courtesan Shinohara from the House of Tsuruya LACMA AC1997.254.2.jpg 1,467 × 2,100;791 KB

-

Courtesans of the Greenhouse LACMA AC1997.254.3.jpg 1,412 × 2,100;1.07 MB

-

Courtisane een hoveling imiterend., RP-P-1961-29.jpg 4,390 × 6,066;4.22 MB

-

Courtisane een hoveling imiterend.-Rijksmuseum RP-P-1961-29.jpeg 1,809 × 2,500;971 KB

-

Courtisane en de Ide Tama rivier De zes Tama rivieren (serietitel), RP-P-1956-598.jpg 4,488 × 6,558;4.07 MB

-

Courtisane en de Ide Tama rivier-Rijksmuseum RP-P-1956-598.jpeg 2,020 × 2,952;3.7 MB

-

Courtisane en de Toi Tama rivier De zes Tama rivieren (serietitel), RP-P-1956-603.jpg 4,392 × 6,662;3.92 MB

-

Courtisane en de Toi Tama rivier-Rijksmuseum RP-P-1956-603.jpeg 1,978 × 3,000;3.25 MB

-

Courtisane Hitomoto uit het Daimonjiya huis-Rijksmuseum RP-P-1956-596.jpeg 1,876 × 2,778;3.76 MB

-

Courtisane Karagoto uit het Chojiya huis-Rijksmuseum RP-P-1952-192.jpeg 1,978 × 3,000;3.58 MB

-

Courtisanes de la maison Tamaya de K. Utamaro (Collection Monet, Giverny).jpg 6,690 × 4,534;27.33 MB

-

Daikagura LCCN2009615596.jpg 7,476 × 4,244;6.69 MB

-

Dessin préparatoire de Utamaro.JPG 1,424 × 2,144;1.56 MB

-

Diptych print (BM 1937,0710,0.116).jpg 607 × 1,600;199 KB

-

Drie paarden, RP-P-1956-608.jpg 4,394 × 6,452;4.47 MB

-

Drying clothes. Woodblock print by Kitagawa Utamaro (CBL J 2538).jpg 13,022 × 6,269;49.68 MB

-

Ebisuko LCCN2008661145.jpg 11,656 × 6,212;15.48 MB

-

Enjoying the Cool in a Garden LACMA M.2006.136.70.jpg 1,385 × 2,100;949 KB

-

Flickr - …trialsanderrors - Utamaro, Kushi (Comb), ca. 1785.jpg 5,556 × 8,577;14.05 MB

-

Fujin tomarikyaku no zu LCCN2008660697.jpg 10,546 × 5,376;10.52 MB

-

Fukubiki LCCN2008660108.jpg 6,633 × 9,559;14.07 MB

-

Futamigaura LCCN2009615459.jpg 6,253 × 9,028;12.63 MB

-

Futamigaura LCCN2009615459.tif 6,253 × 9,028;161.51 MB

-

Geisha`s met sumo poppen, RP-P-2008-237.jpg 4,120 × 6,230;4.04 MB

-

Geisha`s met sumo poppen-Rijksmuseum RP-P-2008-237.jpeg 1,853 × 2,802;3.76 MB

-

Gotenyama no hanami hidari LCCN2008661206.jpg 4,864 × 7,014;7.01 MB

-

Gotenyama no hanami LCCN2008661204.jpg 6,684 × 9,642;11.48 MB

-

Gotenyama no hanami migi LCCN2008661207.jpg 6,682 × 9,636;11.54 MB

-

Hideyoshi and Mitsunari.jpg 735 × 541;197 KB

-

Hinamatsuri LCCN2009615448.jpg 5,992 × 8,736;10.94 MB

-

Ichi fuji ni taka san nasubi LCCN2008660461.jpg 1,024 × 562;132 KB

-

Ichi fuji ni taka san nasubi LCCN2008660485.jpg 1,024 × 521;121 KB

-

Itsuzuke no satsuki LCCN2004676709.jpg 6,420 × 4,353;6.79 MB

-

Kagiya osen to takashima ohisa LCCN2009615449.jpg 5,998 × 9,027;11.32 MB

-

Kashidori fukurō LCCN2008661068.jpg 1,024 × 684;136 KB

-

Kiatagawa Utamaro. Daikokuten drawing himself.jpg 5,242 × 3,407;2.53 MB

-

Kikuzuki LCCN2008660101.jpg 4,742 × 6,856;5.75 MB

-

Kintoki en Yamauba, RP-P-1969-7.jpg 4,274 × 6,412;4.91 MB

-

Kitagawa One Hundred Stories of Demons and Spirits.jpg 350 × 500;56 KB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - Abalone Divers - MFA Boston 21.7353-5.jpg 960 × 505;112 KB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - Catching Fireflies - 1975.98 - Cleveland Museum of Art.tif 7,798 × 3,940;87.92 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - Cleaning Combs - 1930.216 - Cleveland Museum of Art.tif 5,209 × 7,546;112.48 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - Contemporary Beauties Third - 1940.1040 - Cleveland Museum of Art.tif 3,668 × 7,775;81.61 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - Couple in a Boat - 1940.1041 - Cleveland Museum of Art.tif 2,833 × 7,608;61.68 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - Courtesan - 1940.717 - Cleveland Museum of Art.tif 5,417 × 7,780;120.6 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - Figura feminina.jpg 2,723 × 4,200;1.81 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - Kin ki so ga.jpg 429 × 683;299 KB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - No Title - 1949.127 - Cleveland Museum of Art.tif 5,111 × 7,388;108.05 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - No Title - 1949.128 - Cleveland Museum of Art.jpg 2,323 × 3,400;2.05 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - No Title - 1949.128 - Cleveland Museum of Art.tif 4,939 × 7,229;102.17 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - No Title - 1949.129 - Cleveland Museum of Art.jpg 2,285 × 3,400;2.39 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - No Title - 1949.129 - Cleveland Museum of Art.tif 4,975 × 7,402;105.38 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - No Title - 1949.130 - Cleveland Museum of Art.tif 4,747 × 6,461;87.77 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - Serenade - 1943.16 - Cleveland Museum of Art.jpg 2,370 × 3,400;2.01 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - Serenade - 1943.16 - Cleveland Museum of Art.tif 5,240 × 7,518;112.73 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - Two Women by a Bamboo Blind - 1916.1136 - Cleveland Museum of Art.tif 5,317 × 7,940;120.8 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - Woman of the Yoshiwara - 1940.1036 - Cleveland Museum of Art.tif 4,484 × 6,303;80.88 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - Woman of the Yoshiwara with Girl - 1940.1039 - Cleveland Museum of Art.tif 5,330 × 7,791;118.83 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - Woman Representing Good Fortune - 1940.1032 - Cleveland Museum of Art.tif 4,718 × 7,089;95.71 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro - Woman Threading Needle - 1943.20 - Cleveland Museum of Art.tif 5,414 × 7,776;120.47 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro 001.jpg 2,360 × 3,650;9.12 MB

-

Kitagawa utamaro boys hawking party in front of mount fuji 010436 left.jpg 2,215 × 3,200;1.27 MB

-

Kitagawa utamaro boys hawking party in front of mount fuji 010436).jpg 2,235 × 3,200;1.47 MB

-

Kitagawa utamaro boys hawking party in front of mount fuji010436).jpg 2,216 × 3,200;1.43 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro I, Japanese - Two Geishas and a Tipsy Client - Google Art Project.jpg 3,281 × 4,889;4.37 MB

-

Kitagawa utamaro II, due ragazze che leggono una lettera, 1808.jpg 2,796 × 4,122;6.62 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro Omigaya.jpg 1,204 × 600;176 KB

-

Kitagawa utamaro practicing calligraphy020232).jpg 2,215 × 3,200;1.4 MB

-

Kitagawa utamaro, donna con racchetta e bambino con aquilone, 1843-47.JPG 1,548 × 2,244;1.96 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro, Drying Clothes amarohitsu.jpg 13,022 × 6,291;123.87 MB

-

Kitagawa utamaro, fiori di parole, 1790 circa.JPG 2,057 × 3,065;1.63 MB

-

Kitagawa utamaro, guardando in due specchi, XIX sec.JPG 1,740 × 2,472;2.16 MB

-

Kitagawa utamaro, ohisa di takashima e okita di naniwaya, 1790-1800 circa.JPG 2,430 × 3,408;3.99 MB

-

Kitagawa utamaro, pesca da una barca coperta, XVIII sec.JPG 2,476 × 1,308;2.07 MB

-

Kitagawa utamaro, piaceri eleganti, tarda estate a takanawa, XVIII sec 2.JPG 2,816 × 2,112;3.02 MB

-

Kitagawa utamaro, piaceri eleganti, tarda estate a takanawa, XVIII sec.JPG 2,386 × 1,794;2.14 MB

-

Kitagawa utamaro, serie di enigmi figurati, hanaogi di ogiwa, 1797 ca. 01.jpg 1,860 × 2,688;3.26 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro. Court woman admiring cherry blossoms (detail).jpg 3,648 × 5,472;4.69 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro. Court woman admiring cherry blossoms.jpg 5,280 × 2,785;8.71 MB

-

Kitagawa Utamaro. Fun on a summer evening in the garden.jpg 5,721 × 2,929;5.72 MB

-

Kitagawa-Utamaro-Mashiba-Hisayoshi.jpg 2,000 × 2,945;1.82 MB

-

KITAGAWAUtamaro Hideyoshi& his servant Lady.jpg 3,752 × 1,807;7.35 MB

-

Kobikichō arayashiki koiseya ochie LCCN2008660669.jpg 722 × 1,024;159 KB

-

Kushi LCCN2008660667.jpg 5,928 × 8,916;7.59 MB

-

Leeuwendans Waka Ebisu (serietitel), RP-P-1960-11-3.jpg 5,488 × 3,412;3.7 MB

-

Lovers under a Futon LACMA 16.14.107.jpg 1,374 × 2,100;739 KB

-

Mando-子供遊に和賀 万度-Lantern Float MET DP135604.jpg 2,838 × 3,813;3.12 MB

-

Maple Leaves Koyo and Shamisen by Kitagawa Utamaro c1803.png 1,249 × 1,795;3.64 MB

-

Mashiba Hisayoshi.jpg 750 × 1,104;301 KB

-

Matsubaya uchi segawa LCCN2008660784.jpg 6,038 × 9,160;10.47 MB

-

Matsubaya uchi somenosuke LCCN2009615455.jpg 6,031 × 9,091;12.49 MB

-

Matsubaya uchi yosooi LCCN2008660569.jpg 6,180 × 8,820;9.93 MB

-

Matsubaya uchi yoyotose yoyoginu LCCN2008661231.jpg 5,890 × 8,614;9.96 MB

-

MET 1996 85 O1.jpg 1,728 × 1,980;339 KB

-

MET DP135584.jpg 2,555 × 3,806;2.68 MB

-

MET DP135587.jpg 1,276 × 1,941;1.84 MB

-

MET DP135589.jpg 2,548 × 3,814;3.24 MB

-

MET DP135592.jpg 2,568 × 3,843;2.45 MB

-

MET DP135599.jpg 1,215 × 1,920;1.61 MB

-

MET DP135638.jpg 2,673 × 3,911;2.94 MB

-

MET DP135639.jpg 2,796 × 3,848;2.8 MB

-

MET DP135640.jpg 2,654 × 3,902;3.13 MB

-

MET DP135644.jpg 1,315 × 1,916;2.25 MB

-

MET DP135646.jpg 1,296 × 1,932;2.32 MB

-

MET DP135647.jpg 2,560 × 3,892;2.84 MB

-

MET DP135648.jpg 2,629 × 3,903;2.76 MB

-

MET DP135649.jpg 2,622 × 3,866;2.58 MB

-

MET dp135650.jpg 2,589 × 3,851;2.65 MB

-

MET DP135651.jpg 3,098 × 4,000;2.81 MB

-

MET DP135652.jpg 1,598 × 2,000;2.43 MB

-

MET DP141281.jpg 2,583 × 3,878;2.79 MB

-

MET DP141284.jpg 2,431 × 3,867;2.35 MB

-

MET DP141286.jpg 2,576 × 3,853;2.54 MB

-

MET DP141291.jpg 1,299 × 1,931;1.87 MB

-

MET DP141294.jpg 1,291 × 1,921;1.93 MB

-

MET DP141296.jpg 1,336 × 1,941;1.93 MB

-

MET DP141297.jpg 1,299 × 1,935;1.84 MB

-

MET DP141298.jpg 2,588 × 3,864;2.68 MB

-

MET DP144583.jpg 3,952 × 1,993;2.13 MB

-

MET DP144586.jpg 4,000 × 2,038;2.07 MB

-

MET DP144587.jpg 3,934 × 2,029;2.12 MB

-

MET DP144590.jpg 3,917 × 1,959;2.32 MB

-

MET DP144591.jpg 3,920 × 1,967;2.33 MB

-

MET DP144592.jpg 3,883 × 2,012;1.98 MB

-

MET DP144593.jpg 1,946 × 1,015;1.72 MB

-

MET DP144598.jpg 1,759 × 3,923;1.6 MB

-

MET DP144599.jpg 3,905 × 2,848;2.69 MB

-

MET DP144604.jpg 1,910 × 1,466;2.24 MB

-

MET DP144605.jpg 946 × 3,933;847 KB

-

MET DP144606.jpg 1,514 × 3,880;1.34 MB