Shô et les dragons d’eau

L’album jeunesse Shô et les dragons d’eau (Éditions Annick-Press 1995) que j’ai écrit et illustré, témoigne parfaitement mon désir de sortir de l’ombre les peurs et les cauchemars qui ont habité mon enfance et la vie des miens, et de les exposer à la lumière afin qu’ils deviennent énergie créatrice. Le livre a remporté le Prix du Gouverneur Général du Canada en 1995 pour ses illustrations et le texte a été mis en nomination pour ce même prix. La même année, Shô a remporté le Silver Birch Award Ontarien ainsi qu’une médaille d’argent pour le prix littéraire international Korczak en Pologne. L’album sert aussi d’outil dans les cliniques et les milieux scolaires afin d’aider à guérir la psyché des enfants traumatisés par la guerre.

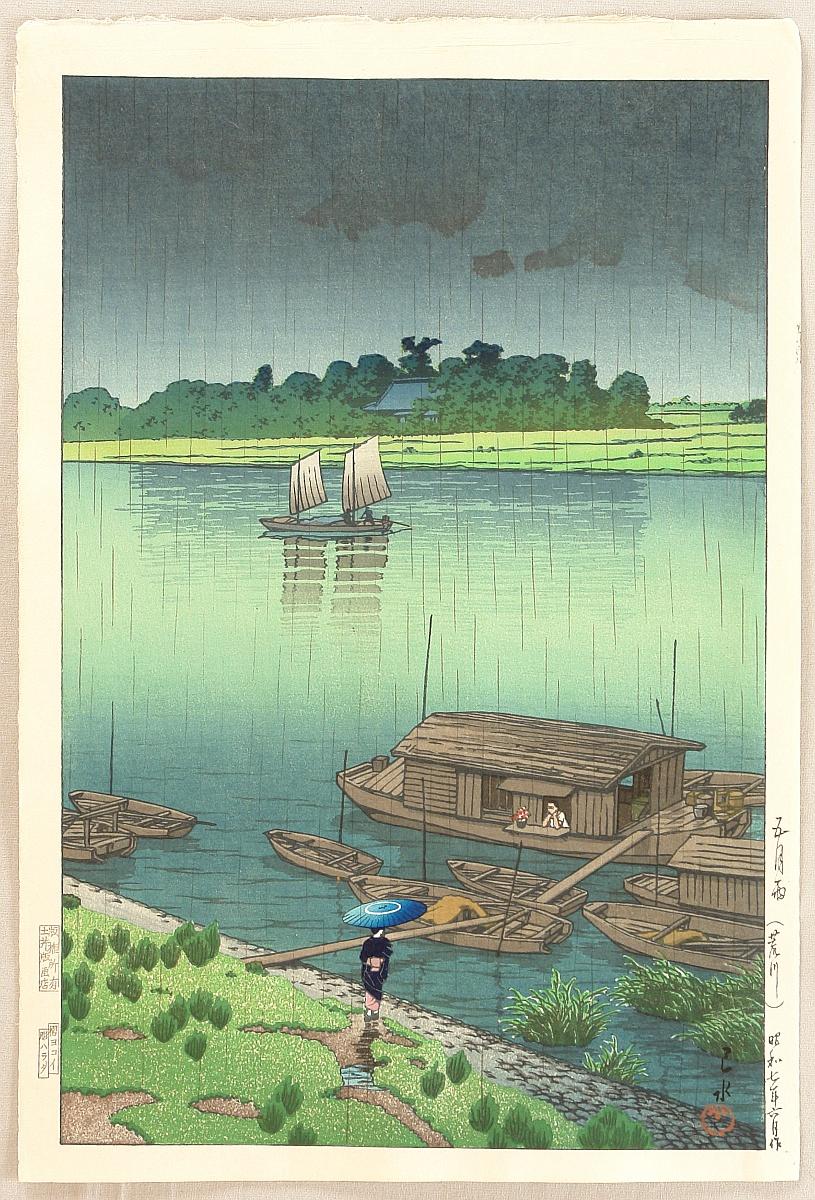

Hokusaï, un peintre graveur japonais du 17e siècle a été pour moi une inspiration importante pour la création des illustrations de Shô. J’ai d’ailleurs dédié ce livre à cet artiste pour l’honorer de son aide et le remercier d’avoir donné à l’humanité un si riche témoignage de la vie rustique au Japon.

L’histoire de Shô et les dragons d’eau est le fruit d’un cheminement spirituel.

J’ai fréquenté durant dix ans un monastère zen qui est de tradition japonaise. Le maître du temple Mukiku Zen Ji nous transmit généreusement ses précieux enseignements. Le zazen (méditation) et le samu (travail physique) étaient des composantes essentielles de la discipline spirituelle. On peut d’ailleurs voir dans le livre Shô une illustration où elle ratisse en vaguelettes du sable dans un jardin de roches. C’est là un jardin inspiré du monastère Mukiku Zen Ji. Aujourd’hui notre maître zen est décédé, mais ses enseignements continuent de nous faire grandir.

J’ai appris que le mot Shô avait plusieurs significations, dont celle d’illumination spirituelle! Je crois bien qu’inconsciemment j’ai choisi ce nom en résonnance avec la qualité d’illumination qui représente mon héroïne. La fillette dans mon histoire est omnisciente, c’est une sage, car elle a atteint « l’autre rive ». Cela signifie qu’elle a atteint la compréhension où l’on reconnaît la nature sacrée de toute chose, celle où l’on reconnaît en soi et en chacun notre « vraie nature » ou notre nature éveillée. Shô est pleinement consciente de cette vie éternelle en elle et, parce qu’elle est pleinement consciente aussi que cette vie est la même dans tous les autres êtres, il lui est facile de les aider. Comme elle voit clair en elle-même : elle voit clair en tous et en toutes les formes de vies. Elle peut donc reconnaître les réels besoins des êtres.

Les trois conditions imposées aux villageois: celle d’arrêter de jeter les cauchemars à la mer, celle d’affronter les démons et celle de partager les fruits de la pêche avec les plus démunis sont les conditions ou les causes altruistes qui permettront à de nouvelles situations plus bénéfiques de se manifester. C’est ce qu’on appelle la loi de la cause à effet.

Ce n’est pas difficile pour moi de personnaliser des objets pour la simple raison que je prends plaisir à donner une allure humaine et fantaisiste à mes arbres, pierres ou objets. Mon inspiration me vient d’une vision que j’ai du monde : comme quoi, tout est vivant. Dans mes illustrations, l’arbre peut marcher, la montagne observer les événements autour d’elle. Une maison habitée par des gens malheureux peut pleurer. Dans l’histoire de Shô, lorsqu’à nouveau le poisson abondera aux repas dans les foyers, les maisons prendront la forme de poissons. Les cheminées en forme de bouche de poisson laissent s’échapper des fumets de soupe. Celles-ci sont un peu inquiétantes, l’odeur du vieux poisson pouvant être épouvantable. Cela nous rappelle la mauvaise odeur de bouche que l’on peut parfois avoir au petit matin et symbolise dans l’illustration que les gens recommencent à accumuler tranquillement leurs cauchemars dans leurs foyers.

Le titre de Shô et les dragons d’eau, ou plutôt son inspiration me sont venus lors d’un festival de cerfs-volants à Montréal. Il y avait un cerf-volant, à mes yeux très particuliers, qui m’a fait vibrer de la tête au pied! Le cervoliste avait enroulé autour de ses reins une longue corde sur laquelle s’alignait une série d’oiseaux blancs découpés. Les oiseaux enfilés sur la corde et agités par le vent montaient dans le ciel en une file étincelante. J’avais l’impression que chaque oiseau blanc était une vertèbre d’une colonne vertébrale humaine géante tendue vers les hauteurs. Le corps et l’esprit du cervoliste étaient très concentrés tout en étant solidement ancrés dans le sol.

À ce moment-là, j’ai senti dans ma colonne vertébrale un flux d’énergie vibrer et s’élever du coccyx vers ma tête. C’était très doux, une sorte de vent intérieur soudainement se réveillait et s’élevait par vagues en moi. Je regardais, un peu ébranlée, le cervoliste très absorbé donner la direction à son cerf-volant. Il m’inspirait. Mes pieds prenaient, à son image, racine dans le sol, car je ne voulais surtout pas m’envoler à tous les vents et risquer de me casser le nez sur le sol. J’avais à ce moment la conviction merveilleuse qu’un même vent, où qu’une même vie, nous animait tous.

Et là, j’ai compris que le feu sacré de l’inspiration, ou qu’un vent subtil, était venu me visiter. Je savais qu’une création naîtrait de cette expérience. Dans une des illustrations du livre, on peut voir un portrait de Shô avec une chute d’eau à l’intérieur d’elle qui représente son jardin intérieur. Un pont en arc-en-ciel derrière sa tête traverse le paysage où des bouddhas méditent. Ce pont de lumière symbolise pour moi le pont reliant la terre au ciel, le physique au spirituel : l’harmonie d’un corps et d’un esprit qui se sont intégrés.

Par la suite, le titre de Shô et les dragons d’eau s’est révélé à mon esprit tout naturellement. Bien des cerfs-volants prennent la forme de dragons en extrême orient. Le terme de démons intérieurs pour signifier nos peurs, culpabilités et blocages émotionnels est familier dans bien des traditions. Les dragons dans Shô symbolisent les peurs ou les démons intérieurs des habitants qui sont refoulés dans la mer (l’inconscient) et qui seront mis à la lumière du soleil (la conscience). À cette condition, les dragons pourront s’élever joyeusement vers le ciel. Ainsi, la peur peut être transformée en bonheur et en inspiration créatrice : tout cela n’est-il pas merveilleux et plein d’espoir?

Le conte Shô et les dragons d’eau met en scène des éléments de ma vie psychique si profonds et si importants que ce récit s’est poursuivi dans un nouveau texte. Les années ont passé dans mon histoire. Shô, dont on se souvient comme d’un puissant modèle inspirant, n’est plus le personnage principal de l’aventure. Le livre a pris la forme d’un petit roman jeunesse, en format poche, accompagné d’illustrations noir et blanc et titré Les cerfs-volants ensorcelés, publié chez Leméac, au Canada en 2004.

Shô and the water dragons

The Shô youth album and the water dragons (Éditions Annick-Press 1995) that I wrote and illustrated, perfectly testify to my desire to come out of the darkness the fears and nightmares that have inhabited my childhood and the lives of mine, and expose them to light so that they become creative energy. The book won the 1995 Governor General’s Award for his illustrations and the text was nominated for the same award. That same year, Shô won the Ontario Silver Birch Award and a silver medal for the Korczak International Literary Award in Poland. The album also serves as a tool in clinics and school settings to help heal the psyche of children traumatized by war.

Hokusai, a 17th century Japanese engraver painter, was for me an important inspiration for the creation of Shô’s illustrations. I also dedicated this book to this artist to honor his help and thank him for giving humanity a rich testimony of the rustic life in Japan.

The story of Shô and the water dragons is the fruit of a spiritual journey.

I attended for ten years a Zen monastery which is of Japanese tradition. Temple Master Mukiku Zen Ji generously gave us his precious teachings. Zazen (meditation) and samu (physical work) were essential components of the spiritual discipline. We can also see in the book Shô an illustration where she rakes in ripples of sand in a garden of rocks. This is a garden inspired by the Mukiku Zen Ji Monastery. Today our Zen master is dead, but his teachings continue to make us grow.

I learned that the word Shô had several meanings, including that of spiritual enlightenment! I believe that unconsciously I chose this name in resonance with the quality of illumination that represents my heroine. The girl in my story is omniscient, she is wise, because she has reached the “other shore”. It means that she has reached the understanding of the sacred nature of everything, the one in which we recognize in ourselves and in each other our “true nature” or our waking nature. Shô is fully aware of this eternal life in her, and because she is fully aware that this life is the same in all other beings, it is easy for her to help them. As she sees clearly in herself: she sees clearly in all and in all forms of life. It can therefore recognize the real needs of beings.

The three conditions imposed on the villagers: that of stopping to throw nightmares into the sea, that of confronting the demons and that of sharing the fruits of the fishing with the poorest are the conditions or altruistic causes that will allow new more beneficial situations to manifest themselves. This is called the law of cause and effect.

It is not difficult for me to personalize objects for the simple reason that I take pleasure in giving a human and fanciful look to my trees, stones or objects. My inspiration comes from a vision I have of the world: like what, everything is alive. In my illustrations, the tree can walk, the mountain observe the events around it. A house inhabited by unhappy people can cry. In the story of Shô, when the fish will abound again with meals in the homes, the houses will take the form of fish. Fish mouth chimneys let out soup scents. These are a little disturbing, the smell of old fish can be appalling. This reminds us of the bad smell of mouth that can sometimes be had in the early morning and symbolizes in the illustration that people are starting to quietly accumulate their nightmares in their homes.

The title of Shô and the water dragons, or rather his inspiration came to me during a kite festival in Montreal. There was a kite, to my very particular eyes, that made me vibrate from head to foot! The collar had wrapped around his loins a long rope on which was lined a series of cut white birds. The birds, strung on the rope and agitated by the wind, rose in the sky in a sparkling line. I had the impression that each white bird was a vertebra of a giant human vertebral column stretched towards the heights. The body and mind of the neckerchief were very concentrated while being firmly anchored in the ground.

At that moment, I felt in my spine a stream of energy vibrating and rising from the coccyx to my head. It was very soft, a sort of inner wind suddenly waking up and rising in waves in me. I watched, a little shaken, the very absorbed kite leader give direction to his kite. He inspired me. My feet took, in his image, root in the ground, because I did not want to fly all the wind and risk breaking my nose on the ground. At that moment I had the wonderful conviction that the same wind, or the same life, animated us all.

And there, I understood that the sacred fire of the inspiration, or that a subtle wind, had come to visit me. I knew that a creation would come from this experience. In one of the book’s illustrations, we can see a portrait of Shô with a waterfall inside her representing her inner garden. A rainbow bridge behind his head crosses the landscape where Buddhas meditate. This bridge of light symbolizes for me the bridge connecting the earth to the sky, the physical to the spiritual: the harmony of a body and a spirit that have integrated.

Subsequently, the title of Sho and the water dragons was revealed to my mind quite naturally. Many kites take the form of dragons in the Far East. The term inner demons to signify our fears, guilt and emotional blockages is familiar in many traditions. The dragons in Shô symbolize the internal fears or demons of the inhabitants who are driven back into the sea (the unconscious) and who will be put in the light of the sun (consciousness). With this condition, the dragons will be able to climb happily to the sky. Thus, fear can be turned into happiness and creative inspiration: is not all this wonderful and hopeful?

The Shô tale and the water dragons depict elements of my psychic life so deep and so important that this story continued in a new text. Years have passed in my story. Shô, who is remembered as a powerful inspiring model, is no longer the main character of the adventure. The book took the form of a small youth novel, in pocket format, accompanied by black and white illustrations and titled The Bewitched Kites, published in Leméac, Canada in 2004.