Along with history and around the world, there are many kinds of ceramics, including porcelain, earthenware, and stoneware, and each of them has impacted different cultures. You may wonder why many fancy ceramics have been called “china” for a long history. It is not only because China has produced high-quality ceramics for thousands of years, but also because Europeans had never seen such porcelain before encountering it in this East Asian country. Starting from the 14th century, China quickly gained a reputation in Europe for having some of the highest quality ceramics in the world. Amongst the many influential ceramic styles originating from China, celadon is one prominent type. Celadon pottery, also known as greenware, is a type of pottery glazed in a transparent jade-like green color. The word “celadon” also refers to the beautiful and iconic jade green colored glaze.

While some ceramics are defined mainly by the material, celadon pottery is defined by its color: a range of green. More specifically, the color is a semi-translucent shade of green that closely emulates the appearance of jade, one of the most precious substances in Chinese civilization. Celadon pottery is just an imitation of this stone. In China, today and throughout its history, jade is highly significant. Jade symbolizes many good things, such as status, spirituality, purity, and health. In 3000 BC, it even became known as “the royal gem”. Celadon came about from years of master potters trying to replicate jade’s exquisite coloring for ceramics.

The origin and name of Celadon

Celadon had appeared before it got its name. Due to the lack of record, the exact origins of the glaze and firing technique used to create celadon pottery are unknown. Some archeologists claim that the celadon glaze technique originated in China during the Shang (1600-1046 BC) and Zhou (1046-256 BC) dynasties when potters began experimenting with glaze recipes. As one of the earliest types of ceramic, celadon pottery belongs to a class of sturdy ceramics made with a high-quality kiln and some sort of green glaze collectively called greenware. Celadon was developed into a distinctive style by the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 CE). During these ancient times, kilns were sometimes inconsistent in temperatures and potters experimented with new glaze recipes.

Though the greenware emerged from around 1600 BC, the name “celadon” was well-known from Europe around the 17th century. There are several opinions on where the term “celadon” came from. One explanation is that it comes from the Sanskrit words for green and stone respectively —“sila” and “dhara”. Another popular explanation for the usage of the word “celadon” in the West is that this word was derived from the 17th-century French pastoral novel called L’Astrée. In this novel, written by Honoré d’Urfé, there is a character named Céladon, who was depicted as a young man dressed in green. The green/blueish coloring typifies nature and is hard to recreate, making it both mysterious and beautiful at the same time.

A brief history of Celadon

For many centuries, celadon was highly regarded by the Chinese Imperial court, before being replaced in fashion by painted wares, especially the new blue and white porcelain in the Yuan dynasty. The similarity of the color to jade, traditionally the most highly valued material in China, was a large part of its attraction. Celadon displays a range of shades, ranging from green-grey to green-brown and everything in between. The most consistent and highest quality workshops were in the Yue region, producing sophisticated greenwares we collectively call Yue ware. This is where the first true examples of celadon pottery seem to have emerged, likely in the 2nd century CE.

Over the next several centuries, Chinese potters refined their kilns, their glazes, and their techniques. Celadon became more standardized and more sought after. The height of celadon pottery production came in the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE). Song Dynasty celadon ceramics achieved the most famous version of this color, which often contained subtle blue or grey hues but very closely imitated the appearance of jade.

For the Song Dynasty, celadon wares could be divided into two distinct varieties. First is northern celadon pottery (960-1450). Northern celadon ware was produced in the Shanxi province, located in northern China. The actual ceramic body was grey and decorated with designs of flowers, waves, fish, dragons, or clouds. An olive-green celadon glaze was then applied, and the pot was fired in the kiln.

However, the highest achievements in this art form are generally seen as belonging to Longquan celadon pottery (960-1279). Longquan wares were made in Zhejiang, a southern Chinese province. The body was essentially porcelain, covered first in a blue-green glaze, then finally achieving the true jade-color glaze that defines celadon pottery today.

Longquan celadon wares were also noted for the simplicity, symmetry, and elegance of the ceramic body itself. While later Chinese dynasties would revive the tradition of celadon pottery, they were emulating Longquan ceramics which have retained their reputation as the pinnacle of Chinese celadon ware achievement.

With the technological development and trade demand, celadon was exported to India, Persia, and Egypt in the Tang dynasty (618–907), to most of Asia (such as Japan, Korea, and Thailand) in the Song (960–1279) and Ming (1368–1644) dynasties, and to Europe in the 14th century. The Song Dynasty was a transformative era for China. Innovations and technologies led to a wealthy and educated population that doubled in size, flourished economy triggered more frequent international trades. In Korea, the celadons produced under the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392) are regarded as the classic wares of Korean porcelain. Celadon was a method that not only dominated the early ceramics scene but became a benchmark of influence for potters across the globe. Today some celadon pieces are so revered that they can reach hundreds of thousands of pounds at auction.

How the Celadon is made?

Celadon is created using stoneware (or porcelain) and fired in a reduction kiln, one of the reasons being is this has the highest reaction with iron oxide, which is used in the glaze. The ingredients are carefully mixed. Some wares were coated with a thin layer of slip containing iron before they were glazed. The method of creating Longquan pottery is incredibly precise (as with all celadon wares) and goes through a cycle of six stages of heating and cooling. The temperatures reach a maximum of 1310 degrees Celsius and through the entire process, the firing of the stoneware glazes is carefully controlled.

UNESCO states that in Longquan pottery there are two types of celadon: “elder brother” (Ge Yao) which has a “black finish and a crackle effect” and the “younger brother” (Di Yao) has a “thick lavender-grey and plum-green finish”.

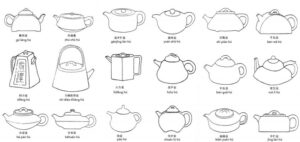

Across countries and centuries, celadon has seen a huge range of shapes, sizes, and uses. Throughout celadon’s high popularity (before it gave way to the newer trend of China’s blue and white pottery style), there were plenty of examples of very rounded bottles and bowls with decorations in the form of everything from floral embellishments to birds.

Longquan Celadon Ware

In the history of Chinese ceramics, there is a saying: “half of the history of the Chinese ceramic is in Zhejiang, and half of Zhejiang ceramics history is in Longquan.” Longquan celadon ware, one successor to Yue celadon ware, emerged around the 10th century from a village named Dayao in Zhejiang province of southern China. The beauty of the glaze color and texture of Longquan celadon ware has attracted ceramic lovers all over the world.

Longquan kiln, founded in the Three Kingdoms and the Jin Dynasty, is one of the six major kiln families in the Song Dynasty and reached its peak in the late Southern Song Dynasty. Initially, during the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127), Longquan ware was covered in celadon glazes ranging in color from faint yellowish-green to a dark olive tone, before evolving to adopt pastel and sea-green shades by the time of the Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279). The elegant shape and exquisite glaze made Longquan celadon to be a model and standard for Song porcelain evaluation.

The most eye-catching feature of Longquan celadon is its gentle and thick, ice-like jade color. Longquan celadon has a thick body, a light blue glaze, and a thin glaze. Among the different green colors, including plum green, pink green, bean green, crab shell green, and so on, plum green and pink green are most outstanding for resembling the color of jade.

What makes the Longquan celadon production process special is its unique method of multiple glazing, an essential glazing method for creating Longquan celadon. Although Longquan celadon has been glazed many times, the color of the glaze is not heavy or fuzzy, but as clear as lake water, with the feeling of a thick glaze. After taking initial cues from both Yue and Yaozhou celadon ware, Longquan celadon ware eventually developed its decorative style, combining elements of impressed designs, spotted splashes, and intricate molded applied. The exquisite craftsmanship of Longquan celadon ware remained prized for centuries. In September 2009, Longquan celadon was listed in the “UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity”.

Hey there! Do you use Twitter? I’d like to follow you if that would

be okay. I’m definitely enjoying your blog and look forward to new posts.